Treatment allows WorkPlay’s Joe Benintende to walk after seven years in wheelchair

Benitende loves tooling around Birmingham in his silver Jeep -- what he calls his unbelievable trade.

After a debilitating 2009 car accident left him wheelchair-bound for seven years, the “Bryant Method’ enabled WorkPlay General Manager Joe Benintende to walk again, making each new day “a gift from God,” he says.

Standing strong: Benitende at his office at WorkPlay in Birmingham. (NewsCenter)

On New Year’s Day, 2009, Joe Benintende says, “I was living in a fairytale.”

Sitting at a stoplight in Hoover, Benintende had enjoyed a carefree New Year’s. Always one to give thanks, he had counted his blessings. Like the Talking Heads melody “Once in a Lifetime,” Benintende found himself “behind the wheel of a large automobile … in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife.”

A longtime fixture of Birmingham’s musical entertainment business, for years he had worked as a promoter with New Era Promotions/LIVE NATION at Oak Mountain Amphitheatre. But in a moment’s time, Benintende’s world came crashing down.

Horrific accident brings Benintende’s world to a grinding halt

Benintende was heavily injured when a young man – who had nine DUIs – crashed into Benintende’s Dodge Durango at about 70 miles an hour.

Benintende literally didn’t know what hit him: His spine was severed.

Treatment allows WorkPlay’s Joe Benintende to walk after seven years in wheelchair from Alabama NewsCenter on Vimeo.

Instantly, he was transformed from a whole-bodied, vibrant man – gifted with the verve to negotiate with some of the greatest musical talents of the age – to a paraplegic in a paralyzed shell from the waist down. Benintende can’t remember the accident.

“My memory is cloudy,” said Benintende. “It occurred to me what I’d gone through when I first got home. I’d spent two months in the hospital, going from St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham to UAB Hospital and back again to St. Vincent’s.”

Benintende’s upper and lower jaws were broken when his face slammed into the steering wheel.

“I still need extensive dental work I hope to someday be able to afford,” he said.

Music was Benintende’s life before his New Year’s Day accident. (Contributed)

Benintende, unconscious, was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital. There, a renowned neurosurgeon performed state-of-the-start surgery to remove four of Benintende’s crushed vertebrae and replace the damaged bone with artificial vertebrae. Benintende also sustained severe injury to the C3 disk in his neck.

“It was pretty high-tech,” said Benintende, 58. “But I lost all feeling from about 1 inch over my belly button, all the way down.” He was transferred to UAB’s Spain Rehabilitation Center under the care of Dr. Keneshia Kirksey, medical director – Spinal Cord Injury Patient Services.

Returning home, Benintende was struck by blinding pain. Having fought substance abuse in his youth, he refused to take painkillers. He’d served as a substance-abuse counselor and, with some partners, helped found Bradford Health Services. For more than 30 years, Bradford Health Services has treated thousands of addicted patients.

Despite the gut-wrenching pain, Benintende never forgot the risks of taking pain killers.

“Sobriety and recovery gave me the tools I needed to get through every day,” he said. “That’s what taught me to have a life with God. You have to fight depression and fight anger after having this kind of injury. First, you ask yourself, ‘Why me?’ Then you have to fight.”

The ‘domino effect’

Stolen moments from life: Benintende greatly missed his involvement in musical events after his accident. (Contributed)

Benintende’s internal organs – bladder, kidneys and gastrointestinal (GI) tract – were paralyzed, along with his legs. He was on a catheter for about seven months.

“I really didn’t regain the sensation, but I learned to evacuate,” he said, in a matter-of-fact voice. “I wore adult diapers for a year. I had no control, and I had accidents at first.”

Benintende emotionally “divorced” himself from his previous life. He was unable to move through his house and sold it for a condo. While laws have made more buildings handicap-accessible, he said, many businesses and restaurants don’t conform. His inability to be mobile – or to see friends at his favorite Birmingham restaurants – was a harsh, new reality.

“I had this incredible career, an incredible life and an incredible wife, and it all got taken away that one day,” he said, incredulously. “From that day on, it all changed. I had a God-filled life before the accident. After that, I had to really depend on God.”

Before the accident, Benintende served as the caregiver to his wife, who suffered from GI problems. Adding to their woes, her problem worsened.

“She became very ill and her whole GI system quit working,” Benintende said. “As a result of my accident, I couldn’t take care of her anymore. It was like somebody started a big domino going, and it went on from there. As far as my wife getting ill, the doctors really never found out why she got sick. They had to remove her entire large intestine two months before my accident.”

His wife started having seizures and strokes. The final episode came when she had a grand mal seizure, and he – wheelchair-confined – had to figure how to pick her up, get her out of the house and into his mobility van.

“I bent down, wrapped her up in a sheet, got her out to the van and drove to the fire department,” he said. “Then I cried for three days. In my life, this was as horrible as things could get without me actually dying.”

Beginning the long road to physical and emotional recovery

“It’s a joy to be able to stand again,” Benintende said. (Contributed)

People often ask Benintende how he made it through the accident and depression.

“A lot of how I got through this was my faith in God,” he said. “I am a firm believer that God has a purpose for everything that happens to you. I’ve always gone to 12-step meetings, and I went wherever in my wheelchair. I was learning how to cope with things, and rely more on God. I am guessing I wouldn’t have made it through this without sobriety and recovery, because that gave me the tools to get through it.”

His life turned around in October 2015, when he talked with some friends he’d known for more than 30 years.

An unusual topic arose.

“They told me, ‘We saw this guy, and he heals paralyzed people,’” Benintende said.

A spark of interest flamed – and was quickly quenched – by Benintende’s logical mind.

“I politely told them this guy was probably a scam artist,” he said. “But they gave me his number. When I talked to him on the phone, he convinced me to come down to St. Petersburg, Florida, to see him. I was probably 80 percent skeptical, 20 percent hopeful that he’d be able to help me.”

Benintende relaxes at home, before his treatment. (Contributed)

‘Healing hands’ activate muscles, nerves and tendons to new life

Benintende took the chance of a lifetime, deciding to try a new treatment created by Ken Bryant, a longtime licensed massage therapist in St. Petersburg.

“He’s a very simple, nonassuming type of person,” Benintende said about Bryant. “What he told me made no sense whatsoever over the phone. He said he’d wake up my body parts, one part at a time.”

When Bryant said that an all-day treatment was $500 – and a four- to seven-day treatment would be needed – Benintende’s heart sunk. The amount may as well have been $5 million.

“I was on disability,” Benintende said. “I was doing good to put food on the table.”

Sensing Benitende’s hesitation, Bryant said, “Don’t not come because you can’t afford it. If you’ll come to St. Petersburg, I’ll treat you.” That was their first and last discussion about money. With hope and trepidation, Benitende decided to make the two-day drive to Tampa. He figured how much gas it would take, and how much money he’d need for food and lodging.

“Even that amount seemed impossible,” he said. “I scrimped and saved.”

The temperatures were comfortable. Benitende loaded up his black Labrador, Angel, and set on the road to Tampa.

“We drove halfway to Tampa, to Valdosta, Georgia,” he said. “I stopped in the parking lot of a La Quinta Inn and slept for six hours. We ended up sleeping in the van for two nights in Florida.

Bryant (left) reawakens Benintende’s muscles, tendons and nerves. (Contributed)

“I was real excited when my foot moved for the first time in six years,” Benintende said, incredulously. “I cried for three hours. After a week, I could move my toes.”

By the third day, Benitende took his first step, using a walker for the first time in several years.

“I could barely move my feet, very minimally,” he said. “It was the most I’d done in six years. Ken worked on me, waking up every muscle, tendon and nerve in my lower body. I could sort of push my knees toward each other.

“I witnessed a lady who was a quadriplegic for 20 years, from disk C5 down, and within an hour, she could move her arms and flap them like a bird,” he said. “If I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

Bryant told Benintende that he’d need to do daily exercises to rebuild his strength. Even now, Benintende lifts his hand – “pinky” finger outstretched – to illustrate the thinness of his legs.

“My legs looked almost like a skeleton,” he said. “They were emaciated from inactivity. I’d have to look down to see where my foot was. I started going to the YMCA every morning to exercise.”

Slowly, he started with basic movements on a special elliptical bike, then progressed to a leg press machine. He exercised three hours a day, including in the swimming pool and the hot tub, which kept his muscles activated.

“I was still in a wheelchair,” Benintende said. “I decided to transition to a walker with hand brakes. I had to teach myself to walk again. Once Ken treats those body parts and they wake up, it’s up to you. He saved my life, no doubt.”

The gift of healing hands

Bryant said he has treated nearly 800 paralyzed patients with 100-percent success. (Contributed)

Working in the medical field for more than 20 years, Bryant, a licensed massage therapist in Florida, applies massage and pressure to patients’ bodies – placing his hands on patients’ leg and back muscles – as a treatment to quell pain and heal injuries.

In 2000, Bryant was working with hospital patients when he noticed that the treatments were bringing about more changes than normally expected. One night, in November 2007, Bryant awoke from a dream with a novel idea: “I wondered if reflexology could go through a paralyzed limb,” he said.

With that thought in mind, Bryant worked on one of his paralyzed patients. Seeing improvement, he tested the treatment on two other paraplegic patients twice a week.

“It took 2½ hours to get through the paralyzed limbs, but there was huge improvement,” Bryant said. “Now, it takes 2½ minutes.”

About three months later, the first patient visited Bryant.

“After being paralyzed for four years, from the chest down, he was able to lean forward and step out of his power chair,” Bryant said.

By 2011, Bryant was treating about 300 people, and those who were paralyzed were all starting to regain their ability to move again, he said.

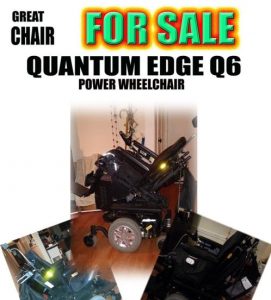

Benintende’s wheelchair is for sale. (Contributed)

To treat paraplegic patients such as Benintende, Bryant said, he “turns on” the back and legs, working first on the mobility of the right leg, then the left leg. He treats the legs thoroughly to revive the muscles, nerves and tendons.

The son of a Southern Baptist minister, Bryant said that it’s the use of “bioelectricity” – a hand form of electrical current that matches the natural electric current of the human body – that promotes healing.

“The treatment works at a 100-percent success rate,” Bryant said. “It reroutes the nervous system. The muscles come back on, but they still need to be built back up. That’s why I tell people they must exercise their muscles to continue building that ability. The usual treatment time is about five days.

“I’ve worked with someone who was paralyzed 55 years, who regained their movement,” he said. “I have had a patient who was missing four inches of his spinal cord, and in three days he was doing 55-pound leg curls. It’s a gift, and I use it to fix as many people as I can. Joe came back really fast because he had ambition. It’s all determination and what they put into it. Patients must work out two hours a day to get their muscles to come back strong.”

Bryant said he has treated 785 patients, all of whom have regained some measure of movement. Many, like Benintende, are exercising and working to push themselves to full recovery.

Similar to Benintende’s original doubts, many in the medical community are skeptical about the use of reflexology and the treatment that Bryant administers, whose usage and results defy the field of traditional medicine. But now, Benintende said he plans to tell everyone he can about how Bryant’s treatment helped him.

On a personal mission to help others

2016 has brought Benintende improved health, a new job and a happier outlook on life. (NewsCenter)

“I have called every Veterans Hospital in the Southeast, trying to tell them about this,” he said. “There’s no reason what this man does can’t be done in every major city in the United States.” He said that not one medical doctor or establishment has offered to observe, document or research Bryant’s treatments.

“I was paralyzed, and now I’m walking,” said Benintende, who showed off his newfound mobility by running down about 25 steps from his WorkPlay office to the first floor. Since he’s regained his ability to walk, Benintende has completed paperwork to discontinue his disability payments and Medicare. Benintende now runs the WorkPlay Venues in Birmingham, serving as general manager. He is finally back in the role he loves: promoting music, movie production and private events through WorkPlay’s facilities, which include a world-class recording studio.

“It’s still hard to stand completely straight,” he said, motioning to the back brace under his shirt. “My spinal cord is still severed, but I can now feel everything in my whole lower body down. According to medicine, I should still be in a wheelchair.

“I still do my exercises every day,” said Benitende, who works 12- to 18-hour days. “It’s a huge building here at work, and I do a minimum of 3 miles a day walking back and forth through the building.” He’s tracked the miles with a pedometer.

The miracle trade: Leaving behind the mobility van for hot wheels

Two of Benintende’s favorites: Angel and his “miracle Jeep.”

With all of his progress, Benitende decided it was time to trade in his cumbersome mobility van. He drove to a Hoover car dealership, intending to look for a Jeep. In all truth, Benitende said, he didn’t have great expectations about what he could get.

“A brand-new wheelchair van is about $80,000, and I got mine used about six years ago,” he said. “I had a 2005 van with 48,100 miles. I didn’t think I’d have much luck selling it.”

He had just parked when a vehicle – a shiny, silver Jeep – pulled in next to him. Benitende struck up a conversation with the Jeep’s owner. He was stunned when the man said he was seeking a mobility van for a family member. The two ended up trading vehicles, with no help from the dealership.

“It was definitely a God thing,” Benitende said, smiling. His “miracle” Jeep Wrangler sits in WorkPlay’s circular driveway every day.

Living a full life after an amazing recovery

Benintende is excited about his new life and greatly enjoys working again. Today, he’s focusing on teaching the concepts of the 12-step program to paralyzed people. The first step, he said, is to admit that one is powerless over paralyzation.

“I try to teach these concepts to other paralyzed patients, who are where I was,” he said. “I’ve applied those steps to my life over the past 30 years.”

Each day, he faces life with new joy, a re-found purpose and hope for the future. After all that he’s endured, Benintende no longer compares life to a fairytale — indeed, he attributes his life to a much higher power.

“I know that God got me through this,” he said.

Editor’s note: For more information, contact Benintende at gmworkplay@gmail.com and see his Facebook page: Joseph Benintende Walking Miracle. Go to Ken Bryant PRS on Facebook to watch Bryant at work with patients.