Red Mountain Theatre Company’s Human Rights New Works Festival to feature ‘Alabama Story’

A 2015 production of "Mandela" was a precursor to the Human Rights New Works Festival. (Photo/Red Mountain Theatre Company)

Kenneth Jones found Emily Wheelock Reed in The New York Times in 2000.

“It was her obituary, and it noted that she was persecuted by lawmakers in Alabama in 1959, when she was state librarian,” he says. “She protected a children’s book about a black rabbit marrying a white rabbit, and later a book by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., from being pulled from the state library. It instantly jumped out at me as a play.”

That play, “Alabama Story,” premiered in Utah in 2015. Its Alabama premiere is the centerpiece of Red Mountain Theatre Company’s Human Rights New Works Festival, which the theater calls “a conversation and a celebration of that which unites us all – our humanity.”

The festival was conceived out of meetings RMTC Executive Director Keith Cromwell participated in leading up to Birmingham’s commemoration in 2013 of the 50th anniversary of major events in the civil rights movement.

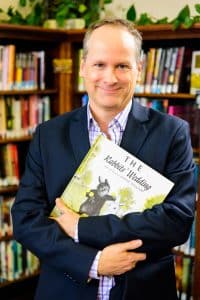

Kenneth Jones holds the controversial book at the center of his play “Alabama Story.” (Photo/Alex Weisman)

“It became a conversation about Birmingham claiming its rightful place as the epicenter where international consciousness was shifted toward human rights,” Cromwell says. “I loved the idea of changing the images that people had of Birmingham. We know that Birmingham was not the only place where the dogs and hoses were happening, but we became the poster child of those horrible circumstances. I’m interested in the opportunity for us to claim a new space where people come to discuss the issues – thought leadership on human rights.”

With plays such as “Back to the Dream,” “Mandela” and “The MLK Project,” RMTC has begun that conversation, but the Human Rights New Works Festival expands the mission.

The four-day festival is bookended March 15 and 18 with a full production of “Alabama Story,” with staged readings of four other works on March 16-17: “The Ballad of Klook and Vinette” (a musical written by Che Walker, Andushka Lucas and Omar Lyefook), Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder’s “Everything That’s Beautiful,” “Mother Emanuel” (a musical written by Christian Lee Branch, Adam Mace and Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj) and “Sam’s Room” (a musical written by Dale Sampson, Trey Coates-Mitchell, Caitlin Marie Bell and Marc Campbell).

The works explore topics such as transgender children, special needs teenagers and an imagined reconstruction of the Bible study at Charleston’s Emanual African Methodist Episcopal Church that ended with nine people being shot to death in 2015.

“What I love is that we have five disparate pieces representing a really great range of information,” Cromwell says. “After each of them, we’ll have a moderated panel and talk-back led by thought leaders and those associated with the topics of each of the plays in Birmingham.” (Tickets are available for individual events or for the entire weekend, with all performances at the RMTC Cabaret Theatre, 301 19th St. North).

In addition, the staged readings are works in progress.

“The goal here is to have the authors hear the words and see how the audience responds and reacts and move forward,” Cromwell says. “The goal is that RMTC might present full productions of the works in the future.”

“Alabama Story” has already gone through that process, including a reading as part of the Southern Writers’ Project at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival. It has since been produced around the country, but RMTC’s production marks its official Alabama premiere.

“I think the play will ‘pop’ differently in Alabama because of its shorthand references and local color,” Jones says. “The play is, in many ways, a love letter to the complexity of Alabama at the time, and it really wants to be about how far we’ve come.”

Jones’ play mixes fact with fiction, alternating between Reed’s fight with state lawmakers and the story of two fictional childhood friends, one black and one white, who grew up in Demopolis, meeting as adults by chance in a Montgomery park.

“Their story bounces off the main story thematically, feeding a larger idea that emerged as I was writing it: This is a play about how character is revealed in times of social, cultural and political crisis,” Jones says.

Though the playwright did a lot of research in Alabama, he grew up in Michigan and lives in New York.

“I view this as an American story, not just a Southern story,” he says. “I believe with enough sensitivity and research that anybody can write about any topic, community or people.”