White bluffs, baked goods, Gaineswood and corn dogs in Demopolis

Janalee Schmidt of Simply Delicious holds cinnamon rolls. (Meg McKinney)

On the 200th anniversary of its founding by French settlers as the Vine & Olive Colony, Demopolis is a progressive city that is successfully merging its colorful past with a promising future.

Little more than a log cabin and the famous white bluffs remain from 1817 but the dream of the early European expedition has been exceeded by a combination of industry on the outskirts and history in the heart of town.

The WestRock paper plant employs about 500 workers, Foster Farms has some 440 employees and Greene County Steam Plant has been providing good jobs for half a century. Demopolis today has top-flight healthcare, a widely respected education system, and recreation opportunities that attract boaters and hunters from across the nation.

Downtown Demopolis has added restaurants and business. (Meg McKinney)

While some older buildings have been lost to the march of time, this city of 7,500 residents has a significant collection of homes and businesses more than a century old. The 10-block downtown is a U.S. Historic District where a visitor can dine at a new restaurant like SVH Bistro or a couple of doors down Washington Street at Stacy’s Café, in the same building where the Alabama Cattlemen’s Association was founded 73 years ago. New businesses are opening their doors in long-closed storefronts, just as modern buildings rise along the U.S. Highway 80 corridor toward Mississippi, offering travelers hot barbecue or comfortable beds.

Demopolis is the gateway to the Black Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway, with its 10,000-acre namesake lake full of bass, crappie, bream and catfish. Eagles, wood ducks and other birds fly overhead, float downstream toward the lock and dam or rest in huge oak and pine trees lining the riverbanks. Boaters from Memphis to Mobile dock at the Demopolis Yacht Basin and the Kingfisher Bay Marina. Foscue Creek Campground has 54 campsites with picnic tables and grills, a nature trail and a boat ramp that are popular with vacationers.

Residents are proud of their small town with big city amenities: a municipal golf course, airport and library, college classes, an active arts council and the Canebrake Players amateur theater group. They boast of the Demopolis City Schools Foundation that began in 1993 with a donation from the Alabama Power Foundation. It has placed more than $1 million into local classrooms and now has a $1 million endowment.

“Demopolis is Greek for ‘City of the People’ and I think that’s very telling,” says Ashley Coplin of the Demopolis Area Chamber of Commerce. “The people here are so caring and have such great character. The world is kind of crazy around us sometimes but we always pitch in to help one another and to boost our town.”

Watching the river floats

A visiting child would easily be awed by the colorful, much larger than life animals, buildings and other paper and wood figures rising in a nondescript warehouse near the northern city limits. There’s a giant green and blue peacock that nearly touches the 25-foot-high ceiling. Nearby are 10-foot-tall lollipops, candy canes, toy soldiers and drummer boys. A miniature version of the historic red-walled St. Andrews Church is on a flatbed trailer, and a huge wooden railroad engine is being hammered together just across from Santa’s sleigh being pulled high into the sky by his reindeer.

Demopolis is the gateway to the Black Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway. (contributed)

Scurrying around all these creations are high school students and retirees — just part of the huge crew of volunteers that each year builds the wheeled floats for the children’s day parade. These and other workers labor in another warehouse nearby getting boats ready for the nighttime water parade that last year celebrated 45 consecutive annual Christmas on the River shows.

“It takes people of all ages, from local third-graders to University of West Alabama students to a large segment of the retirement community, some of them having worked on it for many years,” says Diane Brooker, manager of the Alabama Power Demopolis Office since 2008 and a past chairman of COTR and its street parade. “The people and businesses in Demopolis are so giving of their time, talent and resources.”

Some floats are built by employees of the sponsoring businesses but most are constructed entirely by volunteers. Organizations like the Alabama Power Foundation provide donations each year for materials that help bring to life Demopolis’ biggest one-day attraction, which brings tourists from across the South for events highlighted by the state championship barbecue cook-off.

The night flotilla of glimmering boats followed by fireworks on the Tombigbee River the first Saturday each December has been featured on national television shows, and tops off a week of holiday festivities across the community.

“We have 20,000 to 30,000 visitors for Christmas on the River every year,” says Coplin. “And our volunteers number in the hundreds.”

From dogrot days to dynasty

Gaineswood is perhaps the mother of all Alabama mansions, having risen from a dogtrot house built in 1820 by U.S. Indian agent Gen. George Strother Gaines, to the National Historic Landmark it became through six additions over the next four decades under the guidance of Nathan Bryan Whitfield.

Gaineswood is considered one of the nation’s top Greek Revival houses. (Meg McKinney)

The 6,000-square-foot white-stucco-covered-brick structure sitting on a 5-acre city block south of downtown is considered one of America’s three greatest Greek Revival homes. And the man who made it so is an oft-forgotten genius who excelled in nearly every effort he undertook.

“Whitfield is known as ‘the Jefferson of Alabama,’” says Gaineswood Director Paige Smith, noting that he entered the University of North Carolina at age 12. “If there was a problem, he was going to find a solution, and usually in a very grand manner.”

Whitfield bought more than 5,000 acres south of Demopolis in 1834 but moved his family to town eight years later after three of his eventual 25 natural and adopted children died of Yellow Fever. He acquired Gaines’ house and the surrounding 1,200 acres and immediately began construction, completing additions in 1843, 1847, 1850, 1856, 1860 and 1861 to accommodate his large family and many important guests. College architecture students annually tour the home as a part of their studies.

“He had no architectural training at all, but traveled extensively and was well-read,”’ says Smith. “He knew what he liked, and he designed the entire house based on his experiences.”

Whitfield designs include the nearby First Episcopal Church and the town’s first city square park. Yet, some of his best ideas ended up in the home named for his friend Gaines: the dining room and parlor that mirror each other with 1-ton domed ceilings and cupolas; a flutina player-piano; a 6-foot-tall silver-plated table centerpiece and its rosewood storage cabinet; flat glass on curved surfaces that give the illusion of rounded windows; a massive 12-burner chandelier; 28 identical interior Corinthian columns, each crafted from tools he made; and his hand-carved wooden pineapple gazebo top.

Gaineswood is noted for its marble fireplaces, matching faux-marble baseboards that took an artist 18 months to paint, art-glass transoms by John Gibson (who did similar artwork in the U.S. Capitol), and vis-a-vis mirrors from France that produce a series of 13 reflections.

Today three-fourths of the furnishings are original to the house, as well as photographs, letters and other Whitfield belongings, most of which have been donated by descendants. There is a violin he played (in addition to his talent for the Celtic harp, bagpipes and other instruments). The family Bible lists deaths, births and marriages in Whitfield’s handwriting. His original oil paintings grace several rooms.

In 1923, Whitfield’s granddaughter, Bessie Dustin, sold Gaineswood. Forty-two years later it was purchased by the state and then opened to the public in 1975 for the following year’s national bicentennial celebration. It is open for tours, other than on major holidays, Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m., Saturday from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. and Sunday 2-4 p.m. The Gaineswood grounds can be rented for weddings and photographs by contacting gaineswd@bellsouth.net or gaineswood.org.

“We were very fortunate there was little vandalism while the house was vacant all those years,” says Smith. “We think that was because of all of the ghost stories that were spread through generations.”

Baking bread for the multitude

For seven years, Janalee Schmidt sold homemade bread and cakes, first out of her home kitchen, then, as her business grew, from a dedicated single-wide trailer and later from a double-wide. Dr. Peter Keen liked the pastries so much he asked her to partner with him, and last year he purchased a building in front of Wal-Mart and they opened Simply Delicious.

Pat Toews bakes monster cookies. (Meg McKinney)

“My mother taught me how to bake,” she says. “I’ve been cooking and baking my whole life.”

Now in addition to cooking cornbread, cupcakes and other confections, Schmidt heads a staff of 18 Monday through Friday from 6 a.m. until 5 p.m., serving breakfast and lunch while ringing up cinnamon roll sales and other customer-favorite bakery purchases. She admits the full-scale restaurant business “is a challenge,” but Schmidt relies on the help and guidance of her husband, parents and siblings.

“I use a lot of Mennonite recipes, like for our Poor Man’s Steak. A lot of people ask what it is, which is a variation on traditional hamburger steak with a mushroom gravy,” she says.

The area Mennonite Church has about 150 members who live a simple lifestyle and dress conservatively but have much in common with other Christian denominations. The local congregation isn’t a large enough pool to fill Schmidt’s staff, since many Mennonite women work at home and on their farms. She often goes outside the church family to hire cooks and servers.

“We love all of our employees,” she says. “We’re one big family here.”

Simply Delicious cookies. (Meg McKinney)

Rebecca Handmore was working at a building supply store when Keen went through her check-out lane as she wished him a blessed day. The doctor asked if she would like a job at his business but she learned the pay would be less than she was earning. Handmore has two daughters, ages 10 and 15, and was able to see them only about two hours each day. She decided to gamble on Simply Delicious, which would allow more flexible hours to take her children to school and pick them up afterward.

“I’ve worked at three or four places and they all said ‘We need you to work when we need you,’” says the non-Mennonite Handmore. “They didn’t say that here.”

But the bigger bonus came after the boss saw Handmore in tears one morning. Her employee was about to lose her apartment lease, so Schmidt offered her the single-wide mobile home that had housed the first bakery.

“We were in a place where I couldn’t take a cut in pay,” says Handmore. “But where I took a decrease in income, God took a decrease in my bills.”

A showplace on the edge of the bluff

It’s not that Kirk Brooker doesn’t buy into the romantic legend of one of Demopolis’ most famous citizens building a mansion near his home as a wedding present for a daughter; it’s just that he thinks it was more likely a 10-year anniversary gift.

Bluff Hall opened to the public in 1967. (Meg McKinney)

Brooker says the idea that Allen Glover built Bluff Hall in 1832 for his daughter, Sarah Serena, when she married Francis Strother Lyon, doesn’t quite add up. Her father was a widower for a decade while the wedded Sarah and her husband lived at Glover’s house on Capitol Street.

“When he remarried, she was allowed to move out with her husband,” says Brooker, operations director of the nonprofit Marengo County Historical Society (MCHS). “Glover built houses for most all of his children as a wedding gift, including Bluff Hall. It’s just that Bluff Hall was a very late gift.”

Lyon was a lawyer and planter who served in both the U.S. and Confederate Congress. He drafted a state Constitution that was adopted by the Constitutional Convention. “The man was unreal,” says Brooker.

In 1967, Bluff Hall opened its doors to the public after 135 years. Today, it yet shines as the state approaches its bicentennial.

Restoring the old masonry and frame home after it had been divided into apartments for three decades, the MCHS has returned about 75 percent of the original furnishings to Bluff Hall, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

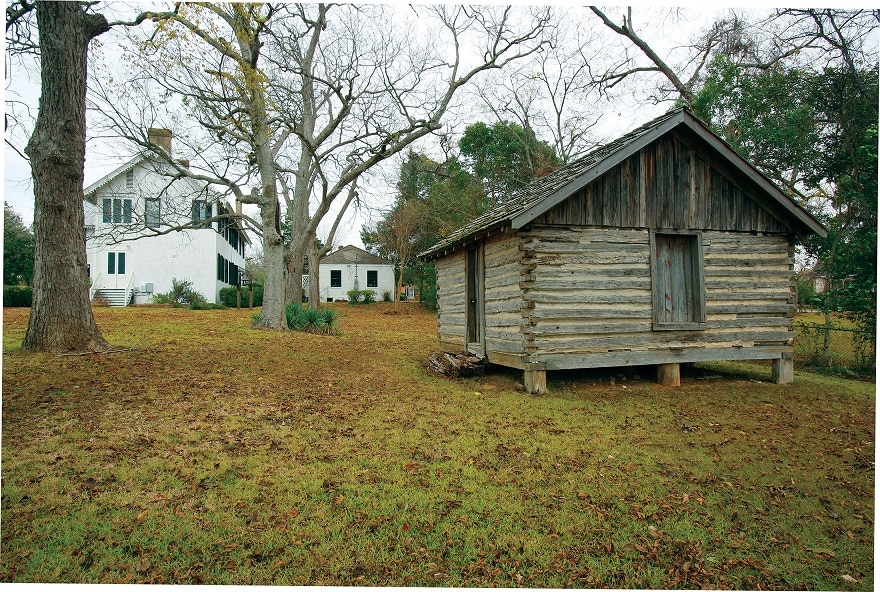

The original cabin near the bluff. (Meg McKinney)

The backyard ends on White Bluff, overlooking the Tombigbee River 40 feet below, which was some 80 feet down before dams pushed up the water level a half-century ago. A log cabin in the backyard was found within the walls of a Victorian house torn down years ago, then saved and moved onto the grounds. “We’re told by experts it is most likely one of the original French settlers’ log cabins,” says Brooker.

Wood columns inside were added to the 10-foot ceilings in 1872 on the owners’ 50th wedding anniversary, purchased from a supply built for, but never used at, Gaineswood. Black and white-veined Italian marble fireplaces are a highlight.

A famous Wilhelm Frye painting of White Bluff includes the artist sitting next to Lyon with his father-in-law’s steamboat on the Tombigbee behind them. A copy of the painting is in the living room.

A dining room, butler pantry and kitchen was added in the late 1840s with a 1-foot-thick brick firewall separating the kitchen from the rest of the house that Brooker says was “unheard of at the time.” In addition to a large fireplace and hanging iron pots similar to those seen in Colonial Williamsburg, there is a cellarette built by slave Peter Lee, who was a skilled craftsman loaned to members of the upper class. Lee was allowed to keep the money from his outside work and eventually bought his freedom.

“The storage unit he built in 1850 is like today’s Yeti,” says Brooker.

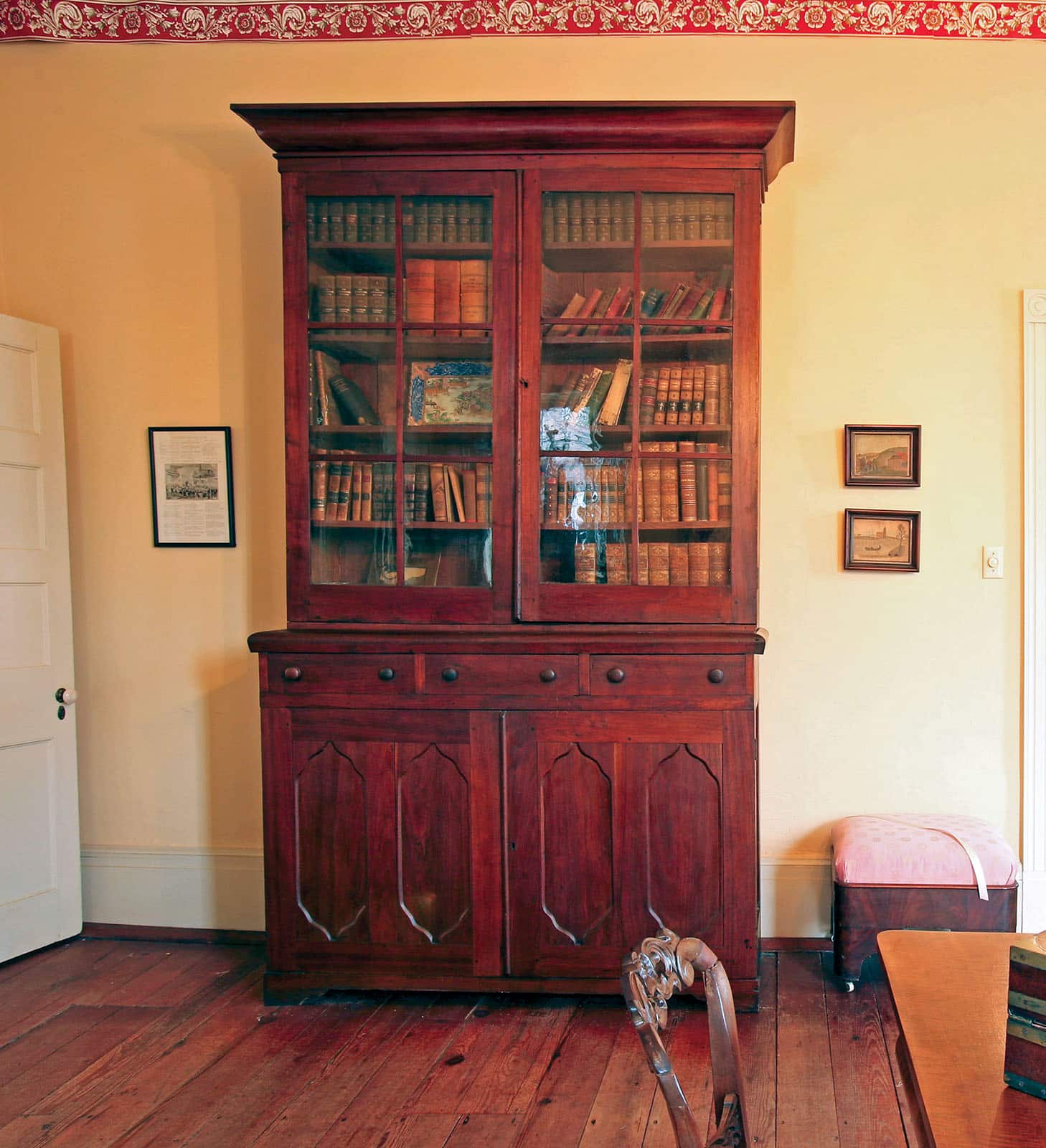

A walnut bookcase nearly touching the ceiling was copied on a smaller scale by Lexington Furniture about 20 years ago and sold nationwide. The bookcase was made by slaves on a plantation near Old Spring Hill.

“I joke with friends that all roads lead back to Demopolis,” says Brooker. “When I was in college, I visited a friend’s house in Atlanta and as I walked into his parents’ dining room, his mom was showing her new china cabinet and saying it was reproduced from a historic house in Alabama, Bluff Hall, and I said, ‘What did I tell you?’”

The birthplace of ‘The Little Foxes’

Kirk Brooker does believe the long-repeated rumor that Lyon Hall is the inspiration for Lillian Hellman’s classic play “The Little Foxes,” which in the 1939 Broadway production starred Tallulah Bankhead and the 1941 movie starred Bette Davis.

The cabinet contains Lyon Hall’s books. (Meg McKinney)

“It matches the description,” says Brooker. “I feel certain when she named the home ‘Lionnet,’ she was referring to the Lyon family.”

Demopolis natives are proud that the popular play has its roots in the 1850 two-story white frame house that takes up a city block near downtown Demopolis. Yet, the majestic 5,000-square-foot structure given by Lyon ancestors to the MCHS in 1997 can stand on its own among Alabama’s significant antebellum homes. It is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Available for tour only by appointment, Lyon Hall was built in 1850 by Francis Strother Lyon’s nephew George Gaines Lyon and his wife Anne Gaines Glover Lyon. It remained in the family until great-granddaughter Helen Nation handed it over lock, stock and barrel. In the 20 years since, much of the furniture and many other things original to the “townhouse” have been returned by family members, or by people who bought items from the Lyons and their descendants.

Four large 18th century Dutch painted panels were donated to line the entrance hall but there is a treasury of beds, sofas, tables, chairs, cabinets, nickel-plated heating stoves, a piano, china, books, vases, quilts, toys and “an unbelievable textile collection” of drapes, clothing and other items that were here before and after the Civil War. The original six massive square stucco-covered brick columns still rise from the ground to the roof, with porches and a belvedere lined by original detailed wrought-iron railings.

The carved post leaning on the wall is all that remains of the gazebo erected every summer a century ago. (Meg McKinney)

Lyon Hall has been preserved rather than restored. It is today much like it would have been for visitors nearly two centuries ago, with unpainted walls and unvarnished heart pine flooring. Peeling paint has revealed that all the interior doors were faux-grained to appear as natural wood patterns. “That, was an amazing artist,” says Brooker.

Uncovered during cleaning was a 4-foot-tall wood carving that is the only remaining part of the gazebo “summer house” that was set up on the grounds and then dismantled each fall.

Although only the first floor is open for rental functions, visitors sometimes are allowed to get a glimpse of the second floor, where volunteers still are cleaning and preparing the rooms and furnishings for future exhibition.

“It’s like they are discovering Lyon Hall themselves when they go upstairs,” says Brooker.

Above the second floor is a large, tall U-shaped attic where servants lived and family travel trunks and other items were stored for safe keeping behind bars and a locked door. A dropdown stairway in the middle leads to an “awesome view” high above the city. Perhaps, before giant oaks lining the river began blocking the view, George and Anne could see their relatives’ homes in the distance.

Bridging the ‘Bigbee with roosters

For nearly a century, one historical event has given Demopolis something to crow about: building the first bridge over the Tombigbee River between Marengo and Sumter counties. In 1919, that span was the last left unbridged on the highway between San Diego, California, and Savannah, Georgia, until auctioneer Frank Derby came up with a unique scheme for funds.

Derby had been successful auctioning bulls for big bucks in Birmingham, so why not give roosters a shot? His committee enlisted famous Americans to help the campaign take flight. Donations of the big birds came from President Woodrow Wilson and the prime ministers of England, France and Italy. Helen Keller donated the only nonrooster, while Gen. John J. Pershing and actors Mary Pickford and Fatty Arbuckle stayed within the rules and sent male chickens.

Seating for 10,000 was erected in Demopolis Public Square and more than 11,000 $2 buttons were sold for admission, barbecue and to view attractions including the roosters being auctioned. Greene County paid $15,000 for an egg laid during the auction by Keller’s bird, while the president’s rooster sold for $55,000, which was the highest of about 900 pledges totaling some $300,000. Unfortunately, the bid by several Montgomery men on Wilson’s rooster didn’t fly, nor did others, and after expenses the auction earned just $45,000.

However, combined with state and federal funding, the bridge opened on May 15, 1925, and 34 years later the name was officially changed from The Memorial Bridge to what everyone already called it: Rooster Bridge.

Last year, Kirk Brooker’s idea of getting an early start on the centennial celebration took off.

“It had been a long-range plan of the Marengo County Historical Society to celebrate the Rooster Auction of 1919,” says Brooker. “We’ve told the story to tourists and students for years, but have not had a large-scale event to commemorate it. The 100th anniversary of the 1919 rooster auction coincides with the 200th anniversary of the state of Alabama.

Last year, they celebrated the 200th anniversary of the city of Demopolis and of Marengo County this year.

The first Rooster Day included the Cock’s Crow 5K, “Stock Your Coop” crafts fair in the public square where the original auction took place, entertainment for all ages and a “rooster auction” of donated items at Lyon Hall.

“The society provides heritage education in the local schools and annual events and programs that help to educate the public about our rich history in unique ways,” says Brooker. “Gwyn Turner, adviser emeritus for the National Trust for Historic Preservation and founding member of the Marengo County Historical Society, taught us to entertain first, educate second. It works.”

A factory with a dog in the hunt

Americans love hamburgers, French fries and fried chicken. Not so obvious, yet clear to any Foster Farms fanatic, is that corndogs hold a warm spot in the tummies of many fellow countrymen.

For 16 hours every Monday through Friday, and sometimes on Saturdays, more than 400 employees in the Demopolis facility prepare, pack and ship 17 varieties of corndogs that end up in schools (a special low-fat, whole-grain frank), Publix, Wal-Mart, Kroger and Sam’s Club stores and Sonic Drive-Ins across the country. The employees make 80 percent of all Foster Farms corndogs, putting nearly half-a-billion of the bread-covered, 100-percent-chicken on sticks into consumers’ mouths.

Despite churning out an average of 1.5 million corndogs each day, the workers have a hard time keeping up with demand in the 130,000-square-foot plant on a 9-acre campus in the Demopolis Industrial Park.

The California-based company purchased its Alabama buildings and equipment in 1994 and has since had four major expansions, the last one doubling the workforce. Most of the employees live within a 30-mile radius.

Foster Farms is constantly upgrading equipment and improving its product, says Human Resources Manager Nick Ancrum.

“There’s definitely a lot more science involved than you would think,” he says.

Before entering the plant, employees must don clean lab coats, new hair and beard nets, and boots that they walk through a sanitizing stream while washing their hands and placing them in disposable plastic gloves. They work in plant sectors that are sanitized each night after the final corndog is packed around midnight.

Each corndog begins when chicken is ground and pumped into natural casings, which are cooked, washed and divided into different-size franks. The casing, though edible, is mechanically peeled off and the dogs are transported up conveyer belts where inspectors remove any imperfect ones. Another machine inserts the wooden sticks and dips long rods containing 20-26 franks each into a batter basin two times before moving them into eight huge industrial fryers. Temperature, moisture and weight are mechanically and manually checked at multiple points in the process.

As the cooked corndogs emerge from the ovens, they fall onto another conveyer where they are checked again for flaws. The product is immediately frozen and sent down another moving belt into a 40-degree room where 32 employees working back to back place from six to 72 corndogs in various-sized boxes. The boxes are shrink-wrapped and moved by forklift to freezers before leaving Foster Farms.

“Everything we produce today will get shipped out today, either to a customer or a buyer’s warehouse,” says Plant Superintendent Buddy Sawyer.

“Miss Edna” takes a customer’s order. (Meg McKinney)

While most of the corndogs leave Alabama’s Black Belt, Ancrum says Foster Farms is proud to keep the payroll local and boost the community through frequent donations of time, food and money. “We want to see Demopolis thrive,” he says.

The Red Barn with a unique hayloft

The line to get a dinner table extends out the front door of the iconic farm building beside Highway 80 East. Despite the parking lot being filled beyond its capacity, the hostess is quick to seat each party. Business is bustling on this Thursday night at The Red Barn, every table filled as customers study the long menu that ranges from seafood to steak to chicken gizzards to barbecue ribs and beyond, most items served with yeast rolls and salad.

A man asks his waitress if “Miss Edna” is still living. After assuring her customer that she is indeed alive, that her mother Edna Brown is actually serving a table just across the way, he insists on speaking with the 36-year employee of the popular restaurant.

“You probably don’t remember me,” he says. “I weighed more than 400 pounds and have lost half of that, but you always waited on me when I was a regular back in 1983.”

Whether she really does or not, Brown makes a point to make the man believe she hasn’t forgotten her “favorite customer.” She smiles and makes polite small talk before returning to her paying customers. The other waitresses are equally adept at pleasant conversation, having perhaps picked up a pointer or two from the veteran, says restaurant owner Roger Roberts.

Edna Brown has greeted guests at The Red Barn for 36 years. (Meg McKinney)

“I have a really great staff,” says Roberts, who bought the barn in 1980, moving from the restaurant his parents started right across the highway. “Miss Edna keeps everyone straight, including me. We have a family thing here. All my help have been here pretty much as long as I have.”

The barn was built in the early 1960s by volunteers using donated materials — including timbers from the old dam’s Lock 5 — for Teddy Porter, a local sports star who was paralyzed protecting his girlfriend in a car accident. Townspeople filled the barn with odds and ends so Porter could make a living, which he did for 13 years before closing the thrift shop.

Roberts, 60, has added on to the original structure several times. The upstairs center section of the barn is now a bar with dining and pool tables. It was voted the Best Local Bar in a poll by The Demopolis Times. He employs 10 full-time workers, including his sister, Sabrina Harrell, and the restaurant is open every day except Sunday “or any holiday that’s a Monday. If it’s Groundhog Day, I’m taking it,” he says with a laugh.

The owner doesn’t serve or cook. He is the “setup man,” working 70-80 hours each week cleaning kitchen equipment such as the fryers and ovens, and preparing all of the food for cooking before and after his chefs and servers arrive. When he’s done in the kitchen, Roberts sometimes steps upstairs to visit with longtime friends and new customers.

“There’s a lot of different kinds of people here and we all get along,” he says as some wave or stop by for a handshake and a word with Roberts. “Demopolis is very fortunate to have a lot of intelligent people. I’m very fortunate to live here. I think this is the kind of place people are going to be looking at to get out of the big towns.”

Proud to serve

Employees of the Alabama Power Demopolis office. (Meg McKinney)

Alabama Power Customer Service Representative Amanda Henderson has worked in the Demopolis Office across from the city square for 14 years, while Valerie Owens has worked there nearly two years after transferring from the Tuscaloosa DOC, where she worked for eight years. Market Specialist Aimee Reynolds has worked for the company 12 years. Their manager Diane Brooker, a Demopolis native, has worked for Alabama Power for 30 years. Cylese Hinton of the Linden Office takes care of appliance sales in the Demopolis Office one day each week. She has been with the company for 18 years. Annie Larkin is a Transmission Lines engineer. Field Service Supervisor Randy Baker is beginning his 40th year with Alabama Power, following 21 years on a line crew and 16 years as a local operating lineman.

“I’m thankful that I have been given the opportunity to work in so many areas of the company and still raise my family here,” says Brooker.

This story originally appeared in the January/February 2017 edition of Alabama Power’s Powergrams.