Tomberlin’s Take: Huntsville’s gain isn’t Birmingham’s loss

Masamichi Kogai, president and chief executive officer of Mazda Motor Corp., speaks at the announcement of the Toyota-Mazda plant coming to Huntsville. (file)

When Toyota and Mazda announced they would build their $1.6 billion in Huntsville earlier this month, there was much excitement from the various city, county and state entities involved in the process and the international media that gathered in Montgomery to herald the news.

A project of this magnitude and its 4,000 jobs is great for Alabama, which has been fortunate to have many such announcements over the years.

But in the days since, some have viewed this great success for Huntsville as a slight against Birmingham.

That would be understandable if Birmingham and Huntsville were competing for the project, but they were not.

“Oh, but Birmingham should have been!” I can hear the naysayers exclaim.

No, it shouldn’t have.

Economic development is driven by a number of factors, but usually two are most critical: labor and property.

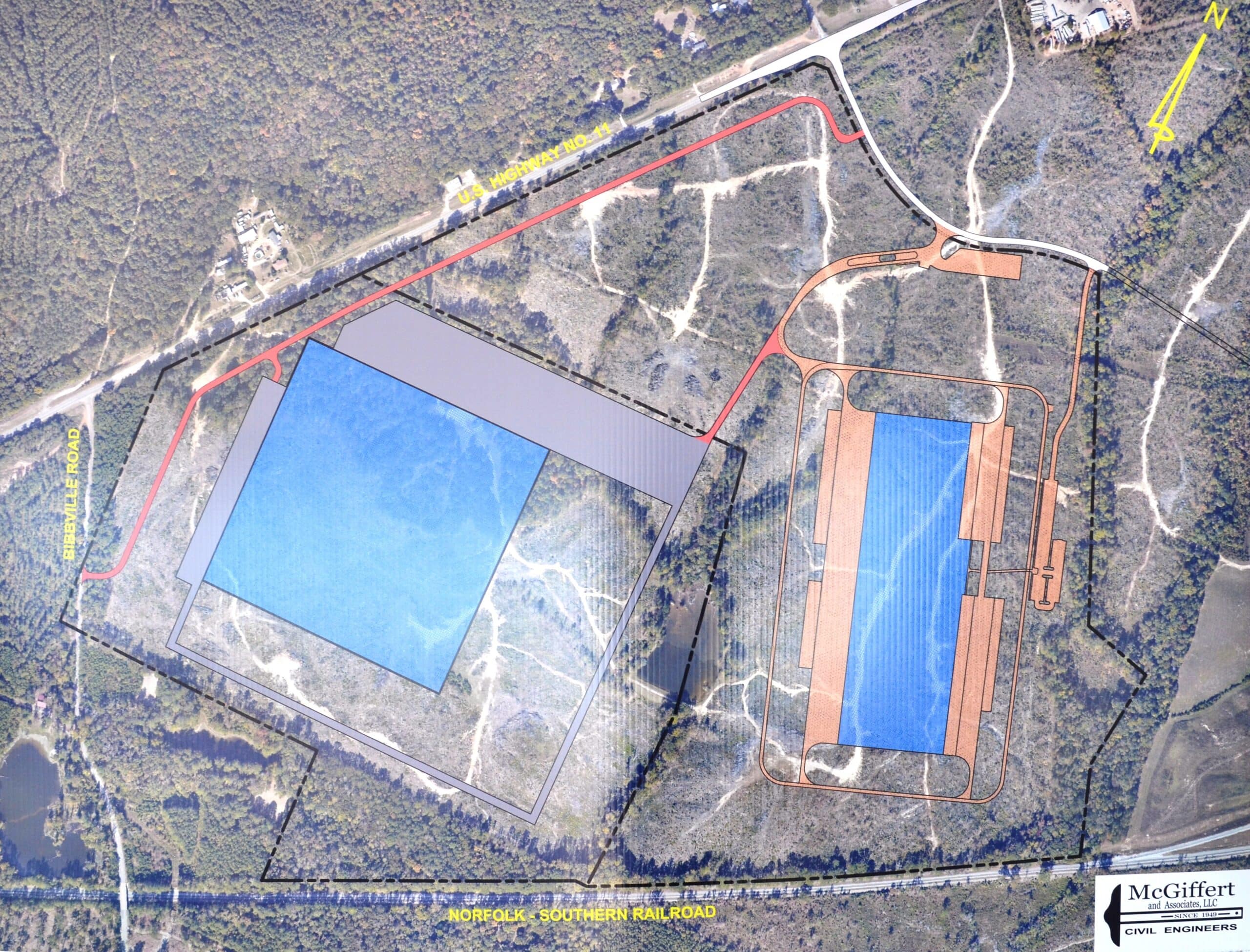

The Mercedes-Benz Global Logistics Center, right, will be 800,000 square feet and the after-sales North American hub, left, will be 1.3 million square feet. (McGiffert & Associates)

With Birmingham’s location almost exactly halfway between the Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance and the Honda plant in Lincoln, no major automaker is ever likely to choose Birmingham for a plant.

The main reason is the labor force. Right now, the two auto plants draw from the Birmingham metro for a good portion of their workforce.

Forty percent of Mercedes workers and nearly 30 percent of Honda’s commute from the Birmingham metro area. Having a new plant competing for those workers is not in the best interest of any of those manufacturers or their suppliers.

But even if labor wasn’t an issue, property would be.

Right now, the Birmingham metro has one certified megasite. The Westervelt Calera Megasite has a number of things going for it. It is a certified AdvantageSite by the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama and it is a Norfolk-Southern Prime Industrial Site. Both designations speak to its location, infrastructure, availability and other factors that would be attractive to an industrial prospect.

At 1,540 acres, the Westervelt Calera Megasite would be large enough for most any project, just not Toyota-Mazda. Because while that project initially was seeking 1,100 acres, it needed an additional 1,000 acres for future expansion.

But this whole discussion is really pointless. Economic development is all about leveraging your assets to compete for new projects or help existing industries expand.

By that measure, Birmingham (and Huntsville and Mobile and Montgomery) are doing well.

One of Birmingham’s biggest asset – besides being the economic hub of the state – is its transportation infrastructure. The number of interstate highways and railroad lines running through the metro along with the state’s largest airport are all beneficial.

Autocar showcased some of its vehicles in downtown Birmingham after announcing its $120 million plant. (Bruce Nix / Alabama NewsCenter)

Combine that with the aforementioned auto plants along with Hyundai in Montgomery, Kia in Georgia, Volkswagen in Tennessee and other auto plants in the Southeast and Birmingham is in a nice spot for automotive suppliers.

Between 2011 and 2017, automotive suppliers announced $1.4 billion in new and expanded operations in the metro area and accounted for 2,342 new jobs.

It’s a good bet that many of those suppliers could pick up some work with the new Toyota-Mazda plant, and Birmingham (once said to be in the triangle created by Mercedes-Honda-Hyundai) is now in the center of the diamond being created by Alabama’s five automakers.

What Birmingham is doing in the automotive sector is impressive, and we haven’t even touched on the innovation economy.

Leveraging assets like UAB, Southern Research and Innovation Depot, Birmingham is carving out its niche in this important economic development area. Most of these are home-grown companies and while they don’t carry the splash of a large auto plant, they can create high-paying jobs and expand the all-important knowledge-based economy.

Those companies have invested more than $300 million in the metro area since 2011 and accounted for more than 1,000 new jobs.

Birmingham has had plenty of economic development success without the need for a single so-called mega-project. (Made in Alabama)

One of the classic knocks against Birmingham has been the lack of cooperation among many of the city and county entities in the metro area. But two examples recently showed how willing municipalities can come together when it counts.

With the AutoCar deal, which brought $120 million in investment and 746 jobs to Pinson Valley, it took Birmingham, Jefferson County, Center Point and the state working together. That project is expected to have an annual impact of $645 million on the region.

More recently, Birmingham’s failed attempt to make the short list for Amazon’s second corporate headquarters saw collaboration between the 10 largest cities in Jefferson County, the county itself, Birmingham, the state and entities such as the Birmingham Airport Authority and the Birmingham-Jefferson County Transit Authority.

Huntsville saw similar collaboration on the Toyota-Mazda project. Mobile saw the same when it landed Airbus. Montgomery did the same for Hyundai. There are numerous other examples from Dothan to Tuscumbia and from Tuscaloosa to Auburn.

If you want to point out Birmingham’s challenges and shortcomings, that’s certainly fair to do. But there is no need to use the victories of Huntsville or Mobile or any other Alabama city to do it. Let’s just celebrate the successes.

Mike Tomberlin is editor of Alabama NewsCenter and a veteran journalist who has covered economic development and business in the state for more than 20 years. Tomberlin’s Take is a column where he takes a closer look at a business or economic development issue.