Organic Zkano socks keep family tradition alive in Fort Payne, Alabama

Zkano founder and owner Gina Locklear shows Mark Malone, a Zkano fan for several years and manager of the Sand Mountain Electric Cooperative, the latest styles in the lobby of the Fort Payne-based mill store. (Lenore Vickrey / Alabama Living)

I first met Gina Locklear on a hot July day in 2010, when a group of Alabama farmers and artisans were showcasing their wares under tents near the lawn of the state Capitol in Montgomery. There were baskets of peaches, handmade soaps, paintings and edibles of various types on display and for sale.

One booth was different. A young businesswoman from Fort Payne was proudly showing off her own Alabama-made product: organic cotton socks. The only color choices were white and natural, but I was intrigued and immediately bought a pair of the “no-show” style to wear with tennis shoes. They have lasted 13 years.

Locklear and the company she founded, Zkano, now ship their American-made socks all over the country.

“Socks are a lot more exciting now than they were then,” Locklear says. At the Fort Payne-based mill that she founded in 2009, she now presides over a successful enterprise that churns out a sock about every three minutes.

She’s no stranger to the sock business, having grown up in the northeast Alabama city once known as the “sock capital of the world.” As recently as the late 1990s, more than half the city’s residents were employed in 150 area sock mills, and it was said that one of every eight pairs of socks in the world was made in Fort Payne.

Gina’s parents, Terry and Regina Locklear, owned their own mill, named Emi-G Knitting (for their two daughters, Emily and Gina), but like many of the mills that once thrived there, it suffered as corporations shifted to buying from companies overseas that could make socks more cheaply.

Yet they managed to keep their doors open. A 22-year-old Gina Locklear graduated from Samford University in Birmingham in 2002. She worked in retail stores in Homewood and sold real estate before deciding she needed to do something to help her parents.

“I liked real estate and the people I worked with,” she says, “but I knew I had to get into the sock business in some way because that was what I was passionate about. It was what I wanted to do.”

Gina Locklear and her parents, Regina and Terry Locklear, who manage the day-to-day operations of the Zkano sock mill. (Lisa Cole)

Going organic and colorful

It took a year of talking to her parents about an idea she had, “making our own organic socks. It took a lot of convincing.” Instead of making socks for athletic-wear companies in bulk, her plan was to make socks for individuals. And not just in white. After a year of research, especially into sourcing organic cotton and dyes, the company was launched in 2009.

“The cotton is grown in Lubbock, Texas, and it’s spun and dyed in North Carolina,” Locklear says. “It was always important to me to source the cotton from the United States.” The process uses no heavy metals and only low-impact dyes, which use less water, and the dye adheres better to the yarn. “It took me a while to find a supplier that would do that,” she recalls, but using safe, nontoxic materials in clothing and everyday products has always been a priority for her personally, and it was no different for her business.

Going organic wasn’t as mainstream then as it is today. “We spent a lot of time trying to tell people why we were organic,” Locklear recalls. “It probably hurt us in the beginning, it was so new. But I wouldn’t change it. Now it’s pretty mainstream. Now people don’t want toxic materials on their body or their skin.”

The business got a huge boost in 2015 when Martha Stewart named it one of the winners of her “American Made Award,” which recognized small business owners across the country. “It was crazy,” Locklear remembers. “I could sit here for an hour and tell you what we learned from that. It helped us grow and gave us the credibility we needed.”

She hired a public relations firm to help get the word out, and that resulted in a cover story in The New York Times’ Style section and a feature on “NBC Nightly News” in 2016.

The results were overwhelming, especially for a small shop with only six employees in the plant.

“I was paralyzed,” she says. “Orders were coming in so fast. Our world changed after that, but we needed it so badly. It just happened when it was supposed to. It got us some loyal customers and the credibility a young business really needs.”

Those loyal customers have stayed. Boosted by the ease of online ordering and a presence on social media, Zkano socks gained even more customers and has been able to expand its number of trendy colors and lively styles for men, women and children.

“When you and I first met, we only had white and natural socks,” Locklear says, “and now we have 70-something shades of colors.

“To go from one shade to all of these is still kind of exciting to me,” she says, showing off the dozens of stacks of yarn inside the mill. The names are creative, evoking nature, food, childhood memories: orange popsicle, mushroom, robin egg blue, dahlia, antique moss.

“Lots of times we will rename a color to make it more appealing,” she says. Using a Pantone color wheel as a basis, the team decides on colors for the dyes. “We don’t usually follow trends,” Locklear says. “We do what we think our customers will like.”

Three women help select and name the different colors. “A lot of times I’m like, ‘What do we call this color?’ And Rhonda (Whitmire, quality control manager) will be like, ‘I know, sugar plum.’ She’s amazing with colors. They are (all) amazing, helping me with style names. It’s a group effort.”

Gina Locklear checks a sock with Vance Veal, plant manager and master technician, who has been with the Locklear family since her childhood. (Lenore Vickrey / Alabama Living)

Unexpected inspiration

Design inspiration can come from unexpected places. For example, wholesale coordinator Mariah Hemphill, who also works in customer service and order fulfillment, was looking through quilt tops made by her great-grandmother and found a particularly appealing floral design. She took photos and showed them to Locklear, and presto, a new design was born. They called it the “Lucille,” named, appropriately, for Hemphill’s great-grandmother and Locklear’s grandmother Lucy.

“It’s my favorite sock,” Hemphill says.

Once colors and designs are in place, it’s up to Vance Veal, plant manager and master technician, to make it all happen. He has been with the Locklear family since Gina was 12 and has largely taught himself how to program the sock-knitting machines to weave the yarns in the patterns required for each sock.

“He’s been there every step of the way,” Locklear says, helping transition the mill from making basic white athletic socks to footwear with colorful stripes, flowers, animals, mushrooms, even Bigfoot (that design is called “Into the Wilderness”). A popular men’s design was “Retro Stripes,” based on some of the first socks her parents’ mill made in the early 1990s. Those quickly sold out.

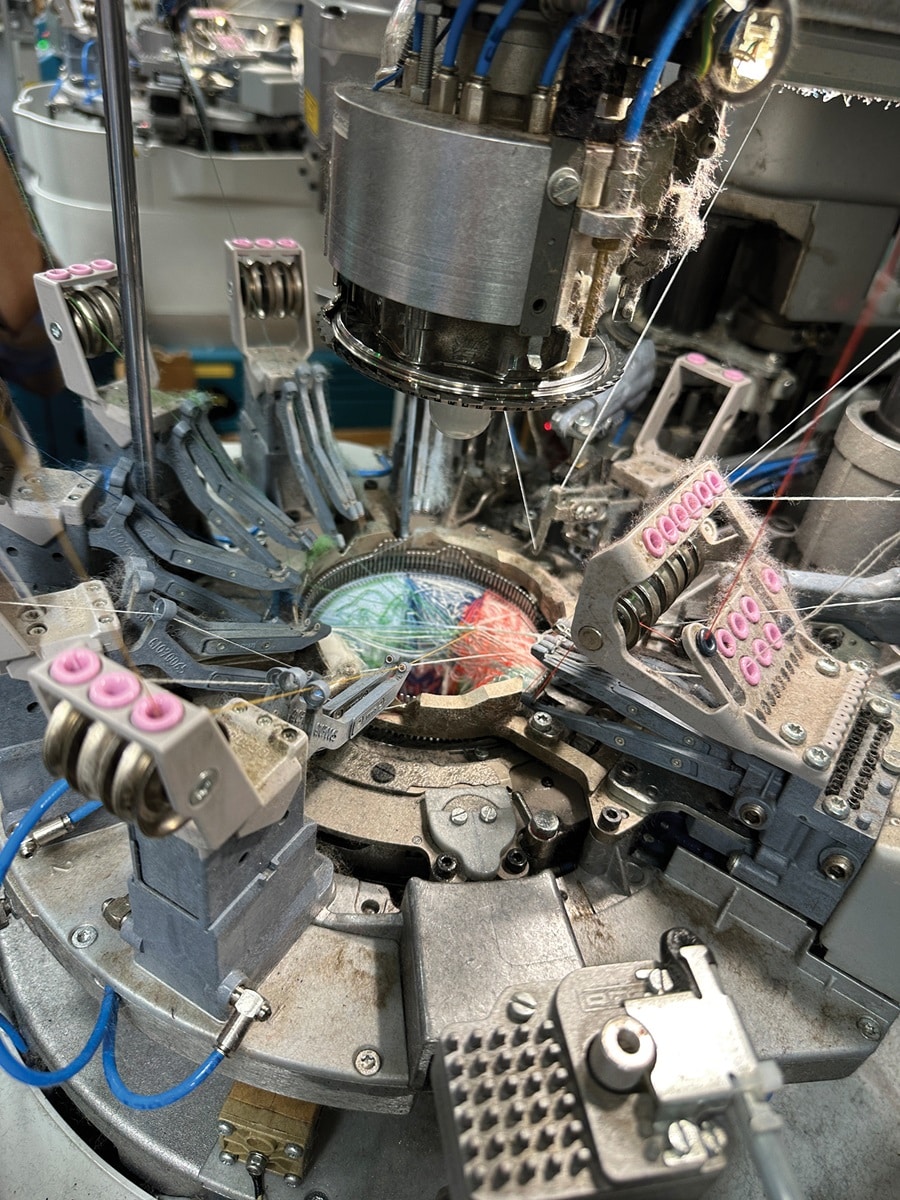

A look inside a sock-knitting machine as multiple colors of yarn are woven into what will soon be a new sock. (Lenore Vickrey / Alabama Living)

Also helping in the manufacturing part of the mill are knitting technicians Guillermo Bautista and Kenny Young. And Locklear’s parents continue to play a vital role, managing the day-to-day operations of the mill. “Without them here to run the mill, I’d have to move to Fort Payne full-time,” says Locklear, who divides her work week between Fort Payne and her home in Birmingham, where she lives with her husband.

Once knitted, socks are rinsed, dried and “boarded,” or placed on specially shaped fitters to remove wrinkles. Whitmire is joined by Hemphill and Maria Pascual, who meticulously check each sock for any flaws before it’s put on the shelf for sale. Any socks with flaws, dubbed “irregulars,” are donated to homelessness shelters and community organizations. Those that can’t be donated are recycled for use in carpet padding in the automotive industry.

Before leaving the plant, each sock is carefully checked by a team including Mariah Hemphill, Rhonda Whitmire and Maria Pascual. Any irregulars are donated to homeless shelters and community organizations. (Lenore Vickrey / Alabama Living)

Holiday sales were steady, with the popular Elf Stripe design (one with lime green stripes and red toes and heels, and another with the reverse) selling out. A consistent top-seller last year was the “Wildflowers” floral design with a hunter green background (named “Fir”), and it’s expected to continue to be popular in 2024. For spring, Locklear says, “We will have a new floral design, probably several. We want to find ways to do more colorful types of basic socks, and make them more interesting, for men and women.”

While Zkano doesn’t plan to expand its operation, it does want to grow its customer base.

“We want to be reaching a lot more people who are looking for products made in the USA,” Locklear says, “so we can employ more people here in town.

“And we want to keep our focus on socks. That’s what we’re good at, and we want to continue doing that.”

To learn more, go to zkano.com. Follow the company on Facebook and Instagram.

This story originally appeared in Alabama Living magazine.