African-Americans have shaped Alabama’s and America’s cuisine

African-Americans have helped define what is Southern cuisine. (Images left-right/top-bottom: Library of Congress, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Library of Congress, Library of Congress, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Alabama Department of Archives and History)

If you are what you eat, Alabamians are barbecue and banana pudding, fried chicken and pork chops, pound cake and pecan pie, fried green tomatoes and okra, catfish and shrimp, grits and greens, peach cobbler and sweet potato pie, buttermilk biscuits and sausage gravy, sliced tomatoes and macaroni and cheese, pimento cheese and boiled peanuts and so much more.

Food flavors Alabama’s rich history and culture, helping define who we are as a people and state. But who defined the food that defines us? In large measure, it has been African-Americans.

Beginning with slavery through the Civil War and Reconstruction, from brutal, segregated Jim Crow days through civil rights tragedies and triumphs, to today when we celebrate food and cooking and restaurants and chefs, African-Americans shaped our cuisine. From the time Africans were forced into slavery in America, they and their descendants influenced and enhanced what we eat and grow in Alabama, across the South and the rest of the country.

Alabama cookbook collection provides clues to African-American influence on Southern food from Alabama News Center on Vimeo.

“The introduction of enslaved African people to the region in the early 18th century drove … cultural and culinary exchange,” wrote Dana J. Alsen in “The Alabama Food Frontier,” a recent report commissioned by the Southern Foodways Alliance for the Alabama Department of Tourism. “Antebellum Alabama foodways were a melting pot of international cultures. European and African traditions became most pronounced.”

New foods brought from Africa in the holds of slave ships soon filled that melting pot and became staples in Alabamians’ diets as well as crops for farmers.

“We have stories of Africans literally hiding seeds in their hair so certain crops like okra and some of the spices that are common now in our diets were brought over literally on the bodies of enslaved Africans,” said Derryn Moten, chairman of the Department of History and Political Science at Alabama State University in Montgomery.

New cooking techniques

In recent years, culinary historians and writers have credited Africans with introducing many new cooking techniques (for example, one-pot cooking, deep-fat frying and using smoked meats as seasoning) as well as dishes to the New World. They created gumbo, an adaptation of a traditional west African stew; stewed tomatoes and okra; corn cakes, grits and shrimp and grits; hoppin’ John, jambalaya, red rice and other rice-based dishes; collards and other greens; chow-chow and other pickled vegetables; boiled peanuts and peanut soup; and chitlins and cracklings, among other foods.

“By the mid-19th century, the most influential and popular American cookbooks all contained recipes featuring African ingredients, including okra, field peas, eggplant, greens, cayenne pepper, sesame seeds and peanuts,” wrote Emily Blejwas, formerly of Auburn University, in the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

What those cookbooks written by and for whites did not contain was proper credit for black cooks. As John Egerton, a founder of the Southern Foodways Alliance, wrote in the foreword to “The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks”: “Long before the South or the nation as a whole got around to debating the deeply fraught social issue of racial integration, the South had thoroughly and indivisibly integrated its food. This was not done with foresight or intention; it simply happened in the prescribed course of events as the black minority did most of the work and the ruling white majority took most of the credit.”

Most historical accounts of American food traditions have long ignored the role African-Americans played. In “The Jemima Code,” which won a prestigious James Beard Award in 2016, author Toni Tipton-Martin documented the contributions black women and men made to America’s culinary landscape. She also sought to dispel the worn-out “Aunt Jemima”/“Mammy” stereotype of African-American chefs, cooks and cookbook authors that “diminishes knowledge, skills and abilities involved in their work, and portrays them as passive and ignorant laborers incapable of creative culinary artistry.”

“The Jemima Code” and an array of books such as Vertamae Grosvenor’s “Vibration Cooking,” Jessica B. Harris’ “High on the Hog, a Culinary Journey from Africa to America,” Judith Carney’s “In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World” and Michael W. Twitty’s “The Cooking Gene” seek to recognize how important African-Americans have been to American cuisine.

Setting the table

They and others in recent years have documented through historical records the role Africans played in setting the table, so to speak, for what became Southern food. They relied on journals and diaries of slave ship captains, slaveholders’ letters, plantation records and cookbooks.

Kelley Fanto Deetz, author of “Bound to the Fire: How Virginia’s Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine,” wrote in the Smithsonian magazine last year of the transformation that occurred in what were known as “receipt books.” These handwritten cookbooks from the 18th and 19th centuries were put together by slaveholding women.

“Early receipt books are dominated by European dishes: puddings, pies and roasted meats,” she wrote. “But by the 1800s, African dishes began appearing in these books. Offerings such as pepper pot, okra stew, gumbo and jambalaya became staples on American dining tables. Southern food – enslaved cooks’ food – had been written into the American cultural profile.”

Who deserves credit for, or ownership of, Southern food remains “a contentious question,” said Kate Matheny, outreach coordinator for Special Collections at the University of Alabama. (Incidentally, Tipton-Martin used a bibliography of UA’s David Walker Lupton African-American Cookbook Collection as “my shopping list” to build her own collection of African-American cookbooks that became the framework for “The Jemima Code.” The Lupton collection of more than 450 cookbooks is one of the largest collections of African-American cookbooks in the country.)

“People that study Southern food are more and more realizing that at the bedrock level, what they know as Southern cuisine is essentially black food for any number of reasons,” said Matheny, who has researched the Lupton collection and many other cookbooks in UA’s Special Collections.

One of the most important reasons, she said, is that during our country’s early history, many white Southerners “were eating food cooked by enslaved Africans.”

“They were bringing over the skills they knew, the kinds of foods they knew how to cook. … And it wasn’t the same as African food. It had become its own distinct thing,” she said.

Holy trinity

The holy trinity of what would become Southern food was greens, pork and corn, Matheny said, and Africans were unfamiliar with pork and corn.

“When you begin to put the pig and the corn and the greens together, it makes something new, but at the foundation of it was the people who were cooking it and the sensibility they brought to it, the spice they brought to it,” she said.

The Africans who were cooking two centuries ago as well as today’s African-Americans cooking the food Alabamians know and love deserve recognition for their part in our state’s food traditions. Among the food pioneers and today’s icons and rising stars that Alabama NewsCenter is honoring during Black History Month are:

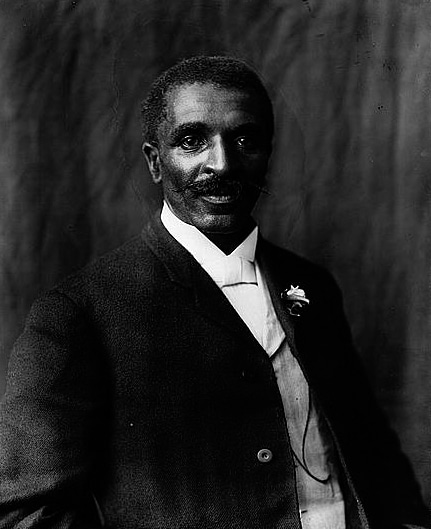

George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute, 1906. (Photograph by Benjamin Frances, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Plato Jones, a former slave whose barbecuing skills were so renowned the United Daughters of the Confederacy asked him to cater a luncheon for Confederate veterans for the unveiling of the Confederate memorial on the Limestone County Courthouse Square in 1909.

- George Washington Carver, who garnered worldwide fame at Tuskegee Institute for his research into sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas and especially peanuts.

- Vera Beck, who left Athens in 1955 in search of better opportunity, landing in Cleveland, Ohio, where she became the test kitchen chef for the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper and a mentor to Tipton-Martin.

- Georgia Gilmore, who fed civil rights leaders during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and became a favorite of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

- Martha Hawkins, dubbed “little Georgia Gilmore” by Gilmore’s son Mark because of her cooking skills, who overcame myriad challenges to open Martha’s Place restaurant in Montgomery.

- Juliette Flenoury, who began her food-industry career at Birmingham’s Greyhound Bus Station and then spent more than four decades cooking for the Mountain Brook Club, where she became known for her corn pones and much more.

The desserts Dolester Miles creates for Highlands, Chez Fonfon and Bottega often combine tradition with imagination. (Karim Shamsi-Basha / Alabama NewsCenter)

Dolester Miles, who grew up in Bessemer watching her mother and aunts bake cakes and is now an acclaimed pastry chef at Birmingham’s Highlands Bar & Grill and won the coveted James Beard Award in 2018 for Outstanding Pastry Chef.

- Duane Nutter and Reggie Washington, who opened One Flew South, a fine dining restaurant in Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport, before launching Southern National, one of Mobile’s and Alabama’s, most buzz-worthy restaurants.

During Black History Month, Alabama NewsCenter is celebrating the culture and contributions of those who have shaped our state and those working to elevate Alabama today. Visit AlabamaNewsCenter.com throughout the month for stories of Alabamians past and present.