Dr. Dennis G. Pappas Sr. has a passion for collecting and storytelling

Dr. Dennis Pappas Sr.'s office at home is one of many rooms that houses his extensive, eclectic collections. (Erin Harney / Alabama NewsCenter)

Dr. Dennis G. Pappas Sr. could not have scripted a more memorable encounter. The year was 1970. As Pappas strolled down Atlanta’s Peachtree Street, a “snake oil” salesman spotted him as an easy mark and approached.

Pappas recounts what happened with glee:

“A medicine man came up to me and wanted to sell me a bottle of snake oil. I didn’t even question his price. I just paid him what he asked for that snake oil. I was so excited that a quack saw me as a sucker,” Pappas says.

His laughter explodes like one of those bottles shattering on concrete.

Pappas holds a tooth that hung outside a barber shop in the 17th century. Barbers of the time also were dentists. (Erin Harney/Alabama NewsCenter)

Clearly, Pappas loves telling this story. It is one of thousands of stories he has gathered over more than five decades of collecting, much of it centered on medicine, particularly quack medicine. Pappas, who will turn 86 later this month, is a well-known ear specialist in Birmingham who still practices a day and a half each week.

His fourth exhibit of medical artifacts at Birmingham’s McWane Science Center is titled “A Sure Cure for Every Complaint! The History of Quack Medicines.” Now on display, it includes dozens of quack medicine bottles from days gone by that promised “cures” for seemingly every malady known to humans: cancer, syphilis, malaria, tuberculosis, diphtheria, cholera, nausea, stomach ache, constipation, diarrhea, menstrual pain and more.

Every bottle tells a story. Here are three of Pappas’s favorites:

- Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. By 1900, Lydia Pinkham, along with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, was one of the most recognizable people in America. She plastered her likeness everywhere to sell Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. “She died of a disease she claimed her medicine cured,” Pappas says. Pinkham’s compound claimed to cure all “female issues,” and women were encouraged to write to her about their ills. Pinkham died in 1883, and the family did not want her demise to damage sales. So they hid her death for years, and clerks continued to answer the mail in her name. Two decades after her death, the Ladies Home Journal exposed the ruse and, Pappas says, “The sales jumped … doubled!”

- Dr. Pierce’s Medicines. Like the shrewd self-promoter Pinkham, Dr. R.V. Pierce spread his name far and wide, on barns from Maine to California, to sell Dr. Pierce’s Medicines. (Pappas has a photo of himself in front of a Pierce-painted barn in California.) But Pierce was no doctor – Pappas says he went to a school no one had ever heard of – and he ran afoul of the Food and Drug Administration with made-up words such as “anuric” to promote his product’s curative powers.

- Swift’s Syphilitic Specific. Nineteenth century Florida Indian chief Billy Bowlegs concocted the formula that became Swift’s Syphilitic Specific (SSS) tonic. “I don’t know that it cured his bowlegs,” Pappas jokes, “but he claimed he cured a lot of his people with this medicine.” Early bottles claimed SSS cured many terrible conditions, including syphilis and cancer. When the federal government began cracking down on “cures’’ for venereal diseases in the early 1900s, the company changed its product name to Swift’s Sure Specific and said it never intended for anyone to think the tonic cured syphilis.

Pappas’s stories, besides bringing his collection to life, add historical and scientific value, according to Jun Ebersole, McWane’s director of Collections.

“When you have an object, a bottle, it doesn’t mean anything unless you have the information behind it. That’s just standard museum stuff,” says Ebersole, who has worked with Pappas to document and develop stories for his collection. “And so with all of this stuff, it would just be considered stuff at yard sales, just junk, until he writes down everything that he knows about it. Now, the collection is priceless.”

Pappas’s collection, amassed over more than half a century, extends far beyond quack medicine bottles. There are medical devices, instruments and textbooks, glassware, arrowheads and other Native American artifacts, political memorabilia, pinball machines and pop-culture Christmas ornaments. Not to mention movie posters and thousands of movies, and railway paraphernalia, including an actual railway car, in themed rooms at the Pappas home. He also has built collections of his own making: origami, carved boxes for rare books, and carousel animals.

The collecting bug bit Pappas as a teenager growing up in Birmingham’s West End neighborhood. “I loved impressionistic paintings from when I was a teenager, but I knew I could never own one,” he said.

Pappas holds an early version of a machine that measures blood pressure. (Erin Harney/Alabama NewsCenter)

Eventually, he would look for, and find, something similar to own. First, though, came his education to be a physician.

Pappas was supposed to go into the Army during the Korean War but received yearly exemptions from the government to train to be a doctor. In 1962, he finished his residency at New York University in New York City as a head and neck surgeon. Pappas and his New York-born wife, Patti, headed to Germany. The Army captain served as an ear, nose and throat doctor for American soldiers and their families. He also had some disposable income, much of which he spent buying large pieces of furniture.

“I made $32,000 a year and did not abide by the principles of Dave Ramsey,” Pappas says, citing the popular author and radio and TV personality who advocates fiscal discipline. “We spent every penny. In fact, our house (in Birmingham) ended up so big because we made stencils of what we bought over there, and where we wanted to put it.”

In 1964, after practicing for two years in Germany and doing only minor surgery, Pappas felt like he had lost his skills as a surgeon and spent a year doing an otology fellowship in Los Angeles. In 1966, after a year in Washington, D.C., the couple settled in Birmingham, where Pappas opened an ear clinic.

The first collection

Pappas still had a thing for impressionistic paintings, but still saw them as out of his reach. “I found out that glass is impressionistic. You could buy a piece of art glass at that time for 200 bucks. Already, impressionistic paintings were getting into the millions.”

The couple took a trip around Alabama and bought eight pieces of impressionistic art glass – the start of what Pappas considers their first proper collection. Two other events in his first year of practice deepened his love affair with collecting and steered him toward building collections in his own field.

Mrs. Pappas wanted to buy her husband a birthday present for his clinic: the Parke-Davis History of Medicine posters that featured the giants of medicine, such as Hippocrates, Edward Jenner, Alexander Fleming and Louis Pasteur. They had been wildly popular in doctors’ offices in the 1950s, but full sets were hard to come by when Pappas began practicing.

“You could only get parts of sets. You couldn’t get the whole set,” Pappas says. “So finally, she got the idea of calling Parke-Davis. She’s got gall. She said, ‘I want to speak to the CEO.’ She got the CEO.

“He said, ‘Lady, we only have two of those sets left.’ She said, ‘I only need one,’” Pappas says, roaring with laughter.

The CEO sent the full set, at no charge.

About the same time, Pappas treated a patient from south Alabama who gave him a worn, dusty mahogany box partly filled with medicines that she’d found at a flea market. He took the box home and cleaned it, revealing hinges and a lock made of brass. Then began hours of research, which led Pappas to a surprising discovery.

“It was a Civil War medicine box,’’ Pappas says. “Researching it was fascinating.”

The prints of medical giants led Pappas to books and stories about their discoveries, while the Civil War medicine box was a piece of history he could hold in his hands. Both, he says, fueled his passion for collecting items that he says bridge art and science.

Many of those items ended up in the Pappas Ear Clinic in Birmingham’s Lakeview District.

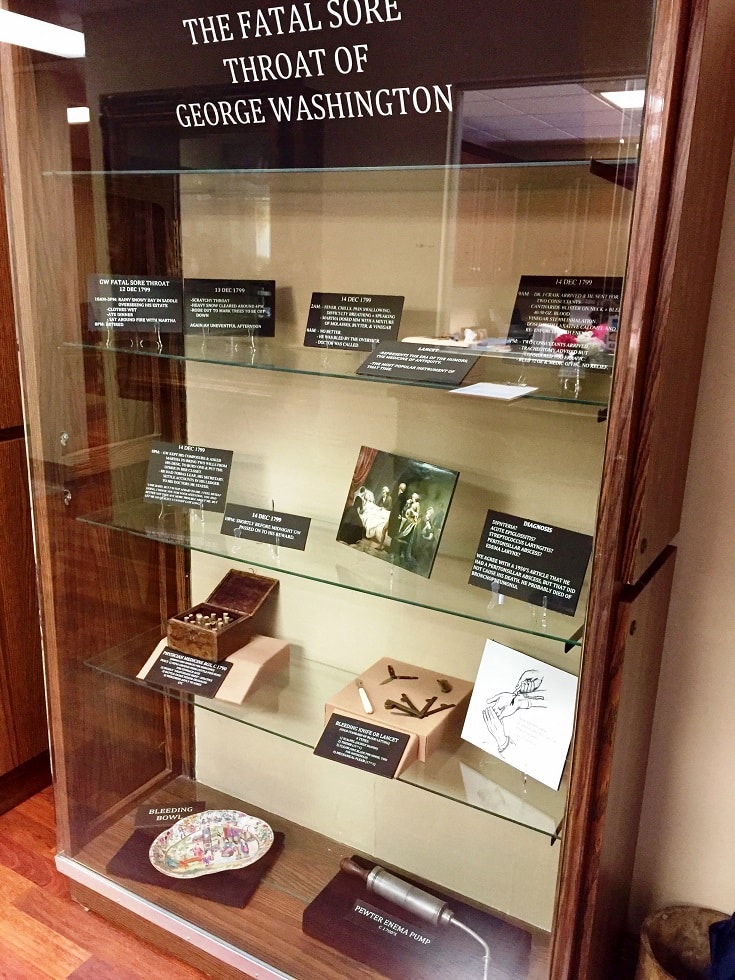

The story of George Washington’s fatal sore throat greets visitors to the Pappas Ear Clinic in Birmingham. (Bob Blalock/Alabama NewsCenter)

The clinic is a museum of sorts, with display cases in the reception area, waiting room and exam rooms housing all sorts of artifacts. Walk through the front door to check in, and the first thing you see is a display about the death of George Washington, who fascinates Pappas. He can talk about the country’s first president for hours, and has lectured on how Washington died.

“He caught a cold and died two days later, which was very unusual,” Pappas says.

Washington developed a sore throat with difficulty swallowing, and fever. His doctors used poultices and an enema, among other treatments they believed would draw toxins from his body. They bled him three times over 24 hours – 100 ounces of blood in all, about half of the body’s total blood volume. Pappas says the overbleeding could have hastened Washington’s demise.

The clinic’s display case on Washington’s death features medical items like what would have been used to treat the president – lancets for bleeding, along with a bleeding bowl; a doctor’s medical box from 1790, complete with vials; and a pewter enema pump.

Other display cases also highlight Washington, from his dancing skills to his documented illnesses treated by doctors; saws and other medical tools used for the most common war operations of the time, led by amputations; and antique glass baby bottles – known as “baby killers,” Pappas says – because babies sucked on their bacteria-laden cloth “nipples” and suffered deadly infections.

“You can literally walk around and see museum-quality artifacts, and at the same time have plenty to read and look at because he gives you the research right there,” says his son Dr. Dennis G. Pappas Jr., who is also an ear specialist and has taken over the practice.

Teachers who are patients have asked if they can bring their students to see the exhibits, the younger Pappas says. And often, he hears from patients who say, “This is the greatest office I’ve ever been in.”

That sort of praise pleases the elder Pappas, who acknowledges the “civic” role his collections play at the clinic, McWane and other venues in which they are displayed. But Pappas admits that satisfying himself is as much the reason he continues to collect more than five decades after he began.

“I could not imagine that out there somewhere was something as old as the hills, something 3,000 years old, 10,000 years old. If I found a Clovis (arrowhead) 10,000 years old, that puts me in the time of the Greek poet Homer,” Pappas says. “That’s meaningful to me. I think that’s amazing to have that.”

Associating an artifact with a period of time, as well as being able to hold that artifact and learn its history, continue to thrill him.

‘First-tier book’

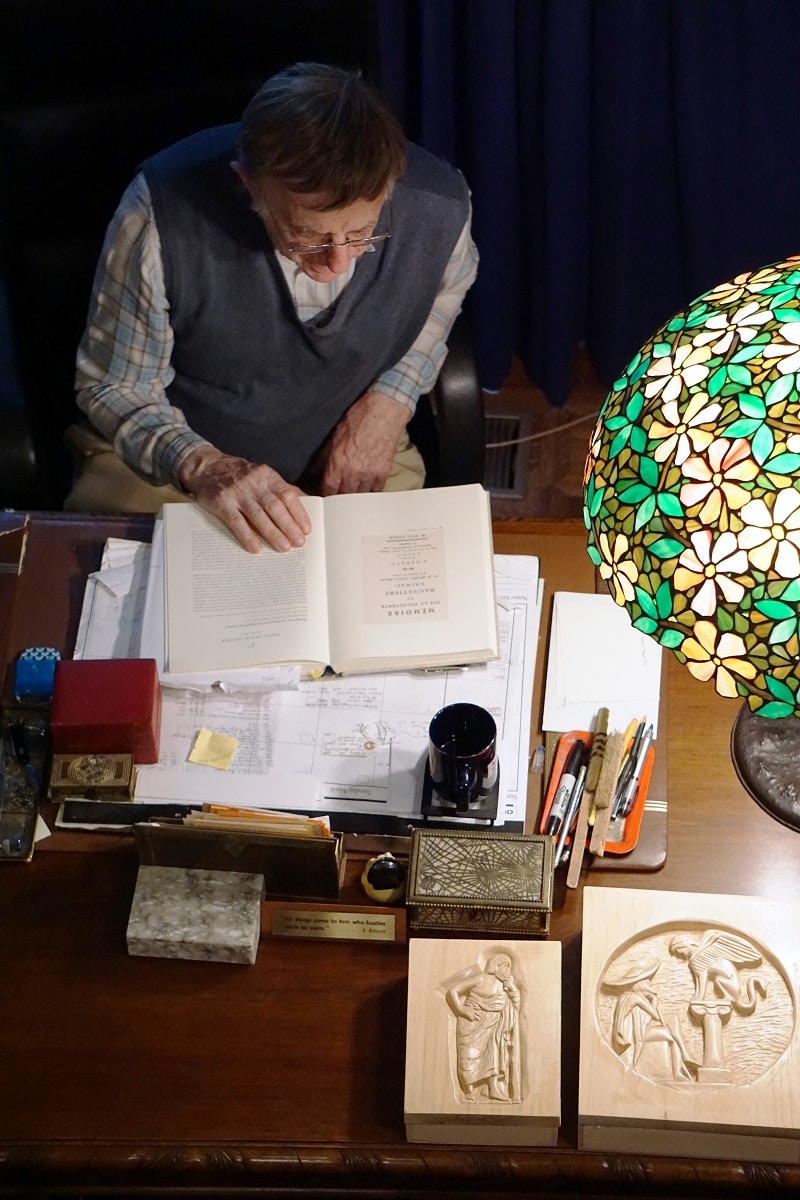

One of the prizes of his collection is a 1763 edition of De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis (The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy), written by Italian physician Giovanni Battista Morgagni. Pappas says Morgagni’s great work laid the groundwork for scientific medicine.

“I shouldn’t have this book,” Pappas says. “I was lucky on this book. This is one of those first-tier books, one of the 100 great books of medicine. Even a blind hog can find an acorn once in a while. That’s what happened to me on this.”

Pappas at the desk he and his wife, Patti, bought in Germany more than 50 years ago. (Erin Harney/Alabama NewsCenter)

Pappas describes himself as a “second-tier” collector who can’t afford to compete with the Silicon Valley and investment banking millionaires and billionaires for first-tier collectibles.

“They don’t care about what medicine is in it, or the history of it,” he says. “They just want it for an investment.”

That’s not what drives Pappas.

“I’ve never really sold anything so I don’t know what the collection is worth,” he says. “It’s what you get for it that shows what it’s worth.”

While he hasn’t sold anything, it’s not because he hasn’t gotten plenty of offers. Pappas tells of one that still tickles him. Pushed into a corner of a spare room in the clinic is an old wooden case with an X-ray machine, often called a fluoroscope, that shoe stores used to fit shoes starting in the 1920s and as recently as the 1970s.

“In the ‘30s when your mother took you in for shoes, she wanted space so that your shoes would last a couple of years while you were growing,” says Pappas, who was born in 1931.

The problem was, the X-rays often seeped throughout the store and salespeople were chronically exposed.

“They put the ax to these things, though this Art Deco unit escaped the wrecker’s blows,” he says. “I got this and a guy from south Florida called me up who knew I got it and he wanted it in the worst way. He said, ‘I’ll give you double what you paid for it.’ I thought, that only makes me think I should keep it.”

Pappas held onto the X-ray machine, along with everything else. Pappas Jr. says that is his parents’ nature. “That generation didn’t throw things away. They kept everything,” the younger Pappas says.

“Every closet in their house is completely full,” he says. “Every closet in this office, and rooms we don’t use, is full with stuff they collect because they just have nowhere to put it.”

A lifetime of collecting

Pappas Jr. doesn’t remember a time in his life when his parents weren’t collecting. He is 55 and remembers family vacations that almost always included his parents dragging their three children to antique stores.

“That was not always fun to do on your vacation,” he says. “But it was always fun when they found something exciting, or really old, or something that looked cool, like an amputation saw from the Civil War.”

The old way of collecting – visiting antique stores and estate sales, and establishing a network of other collectors and dealers around the country who know what you are looking for – is gone. Like so much else, the internet has destroyed that model.

Although Mrs. Pappas always has been involved in acquiring items for the collection, she has blossomed as the internet drives collecting.

“I’m the finder,” she says. “I know how to search. There’s just so many people who don’t know how to list things. They’ll start with ‘16th century, beautiful, exotic,’ and the searches aren’t going to find what’s after that. I know how to search those. I find a lot of stuff but it’s getting more and more difficult.”

She routinely nurses 200 ongoing searches, wading through about 500 daily emails related to them as well as emails from dealers. Bargains these days are hard to come by from dealers, who know the value of what they have, she says.

In addition to being the finder, Mrs. Pappas may also be the enabler.

She says: “If you’ve never seen it, or you’ll never see it again, buy it. Because when you go back, it won’t be there.”

Pappas refuses to pay more than he believes an object is worth, but says some items he let slip away continue to haunt him. Of course, that triggers a story. Over the years, a woman in Maryland sold Pappas “half my collection.” This, even though she sometimes talked him out of purchases – he distinctly remembers not buying a gorgeous box of veterinary instruments with mother of pearl handles.

“Some of the stupid things that I did in life are things I didn’t buy from her,” Pappas says.

When the woman’s husband died, Pappas had a chance to buy his collection of rare golf books. “I should have bought the collection for a few thousand dollars. It’s probably worth hundreds of thousands today. Stupid, stupid, stupid,” he says.

His father’s stories about collecting are pure gold to Pappas Jr.

“He’s a good storyteller. That was always something I remember,” the younger Pappas says. “He still does it. In fact, we go to his house every Sunday night to eat – the family that lives in town, whoever can come to dinner.”

Pappas stands near the ticket office at the “railway station” in his home. (Erin Harney/Alabama NewsCenter)

At the end of the meal, the elder Pappas will give a 10-minute talk, usually related to medical history.

“It’s like he can’t wait for dinner to be over so he can start talking,” Pappas Jr. says.

The younger Pappas jokes that he did not inherit his father’s way with words, which his wife, Kellie, made clear to him.

“She’s the one who said to me years ago, ‘Your dad is such a great storyteller. I just love hearing him. Anytime he wants to tell a story, I want to hear it.’

“I can go tell her the same story, and she’s looking at her cellphone,” Pappas Jr. says, his own burst of laughter echoing his father’s.

One of the younger Pappas’s regrets is not recording his father’s stories.

“I wish I had him on tape or on film telling those stories about each thing. That’s something I should consider doing now, to get him to do that,” Pappas Jr. says.

Easier said than done. The collection is so huge and the elder Pappas’s stories so thorough, that “if you spent an hour a day doing it, it would take forever,” his son says.

Documenting his collection

For the past several years, though, Pappas has been busy documenting his collection in other ways. Father and son over many Saturdays have taken pictures of Pappas’s medical book collection, and Pappas is writing something about each book, his son says. Pappas also has worked with McWane’s Ebersole to put to paper the information and stories he has gathered on the medical quackery items.

“To him it’s another project, and he loves projects,” Ebersole says. “We’re on our fourth show now. To be able to work with him, see him research this stuff and tell me the stories, it’s amazing stuff.”

Just the part of Pappas’s collection related to medicine is astounding, Ebersole says.

“Whoever ends up getting this, whether it’s UAB or some other place, it’s going to be the true history of medicine with some unbelievable stuff,” he says. “There are some stand-alone individual artifacts that are spectacular. But the research he’s done behind these things, and now he’s getting it all out of his head. It’s an unbelievable collection.”