James McCrory: Alabama’s Revolutionary War hero

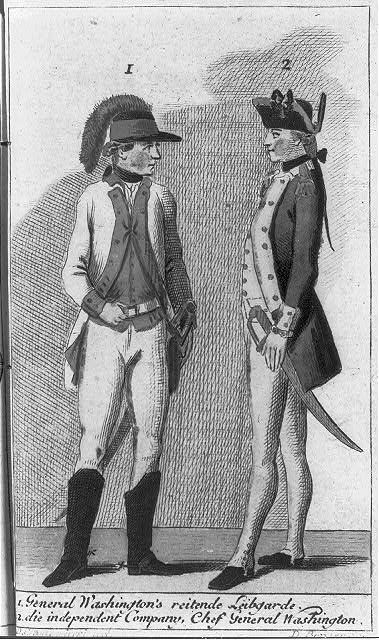

As one of George Washington's personal bodyguards, James McCrory, along with many other soldiers, braved the harsh conditions at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, during the winter of 1777-1778. (Library of Congress)

“In spite of (his) gallant services the committee reported adversely because of some technicality; but as the old hero had then been dead two years he was probably not very deeply affected or disappointed by the decision.”

The black humor of this transcript from a Feb. 4, 1842, meeting of the Committee on Revolutionary Claims describes the committee’s lukewarm recognition of James McCrory’s military service during the Revolutionary War. It also highlights the general lack of recognition that has dogged one of Alabama’s most illustrious Revolutionary War heroes.

This oversight is baffling considering that McCrory saw action in an incredible number of the Revolutionary War’s most famous battles and was a bodyguard to Gen. George Washington before McCrory reached his 20th birthday. His impressive military resume would seem to make him a staple in American history books, but few people outside Pickens County, Alabama, where McCrory spent his final years and is buried, know much about him. This is an unfortunate legacy for a man whose gallantry and service helped this country win its independence.

McCrory lived a varied and interesting life before settling in Alabama. He was born in the village of Larga on the River Bann in County Antrim, Ireland, on May 15, 1758, and he came to the colonies when he was 17, along with his brothers Hugh, John and Thomas. His ship sailed from Belfast, and he set foot on the American continent in Baltimore on July 1, 1775. He headed south and soon settled in Guilford County, North Carolina.

This was a period of restiveness in the colonies, and the nascent colonial independence movement was rapidly gaining traction among newly arrived immigrants. McCrory was no exception. He undoubtedly brought with him across the Atlantic some of the Irish enmity toward the English, and nine months later, on April 15, 1776, he enlisted in the Continental Army for a term of three years. He initially was a company sergeant under the command of his brother, Capt. Thomas McCrory, as part of the 9th Regiment of the North Carolina Line, led by Col. John P. Williams. The regiment marched north and joined Washington’s command at Middlebrook, New Jersey, on June 6.

A 1784 German illustration depicts a member of George Washington’s Life Guard, left, with a company soldier under Washington’s command. James McCrory, later a resident of Pickens County, was a member of the group that personally guarded Washington during the Revolutionary Army’s harsh winter at Valley Forge. (Library of Congress)

For the next five years, McCrory seemed to be in action at practically every major battle of the revolution. He fought at the Battle of Brandywine under Washington on Sept. 11, 1777, and at the Battle of Germantown on Oct. 4. For his performance on the battlefield, he was promoted to the rank of ensign in the Life Guard of General Washington, and was one of Washington’s bodyguards during the brutal winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge.

The next year McCrory saw action in the American defeat at the battle of Stono Ferry near Charleston on June 20, 1779. He later fought in the Battle of Camden in South Carolina, where Gen. Horatio Gates was defeated by Lord Charles Cornwallis’ British troops in August 1780. One thousand American soldiers were taken prisoner at Camden.

McCrory eventually was captured by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s Dragoons, who held him prisoner for five months onboard a prison ship at Wilmington. McCrory hardly could have picked a worse fate than to be captured by Tarleton, who had earned infamy at the Battle of Waxhaws when American Col. Abraham Buford surrendered his forces to him. According to American accounts, Tarleton ignored the white flag and massacred Buford’s men. The sordid affair came to be known as the Waxhaws Massacre and provided strong anti-British propaganda for the colonials. Given Tarleton’s reputation, McCrory undoubtedly feared for his life.

The late Bettye Burkhalter, McCrory’s great-great-great-great-granddaughter, wrote that “the British captured him and held him prisoner for months in only his underwear on one of their ships anchored a safe distance from shore. With each passing month his Irish blood boiled. One night he jumped overboard and miraculously swam through the icy waters to shore.”

His brief imprisonment apparently did not cool his desire to fight the British, and shortly after his escape, he rejoined the Continental Army and served under Gen. Nathanael Greene at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781. He was honorably discharged in the spring of 1782, ending his military career.

On Feb. 28, 1782, McCrory married Jane Gilmore, and the couple moved to Tennessee and started a family. He stayed there until sometime around 1820, when he moved his family (which had grown to 12 children) to Alabama. In 1826 McCrory started buying land in Alabama, and over the next 10 years he purchased a total of 840 acres near the town of Vienna in what is now Pickens County.

McCrory became one of Vienna’s first residents, moving there when the town was in its infancy. Settled in the 1820s, the town was established on the east side of the Tombigbee River as a river port and trading center. The river provided transportation for Vienna’s farmers, who loaded their cotton on riverboats to be taken downstream to Mobile. Today little remains of the town other than a historic marker identifying the site of a former school and the foundations of a couple of houses.

McCrory lived with his son, Robert, in Pickens County, and on June 13, 1829, he was granted a military pension based on his Revolutionary War service. The latter years of his life were quiet, and it appears that this pension and cotton farming were his sources of income during his 14 years in Alabama.

McCrory died on Nov. 24, 1840, at the age of 82. He is buried 5 miles south of Aliceville in Old Bethany Cemetery at the site of the Old Bethany Primitive Baptist Church, a structure that was abandoned and torn down in the early 1900s. McCrory is interred next to his wife, who died 10 months before him. Their marble tombstones stand side by side and are bracketed by a simple red brick monument. The inscription on McCrory’s tombstone reads:

“In Memory of JAMES McCRORY. Who departed this life November 24th 1840 Aged 82 years 6 months and 9 days. The deceased was a soldier of the Revolution and was at the battles of Germantown Brandywine and Guilford Courthouse he was one of Washington’s Life Guard at Valley Forge and served his country faithfully during the war. Peace to the soldiers’ dust.”

One of McCrory’s descendants, Margie McCrory Burrell of Auburn, said in 2012, “I am now 90 years old, but I well-remember the day I walked to my mailbox around 1942 and found a letter with an inheritance check from my great-great-great-grandfather, Capt. James McCrory. My daddy was dead, so his children equally inherited his part. Throughout the years, as I read and watched special programs on television that showed or pointed out that ‘George Washington slept here,’ I glowed with pride knowing my grandfather was one of his bodyguards during the American Revolution. Every time I see President Washington’s portrait or his picture in a book, I remember with pride that my great-great-great-grandfather helped protect this man that led us to freedom and became our first president. That was, and still is, big to me. Real big.”

McCrory did finally get some measure of recognition. In 1986, the Pickens County Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a sign highlighting his military service near the Old Bethany Cemetery entrance, and in 1993 the Alabama State Legislature adopted a resolution naming a section of Highway 14 in Pickens County the “James McCrory Memorial Highway.”

Thomas Ress is a freelance writer who lives in Athens, Alabama. This story originally appeared in Alabama Heritage magazine.