Tomberlin’s Take: Birmingham clearly economic heart of metro, state

Birmingham has been awarded a Smart Cities grant in only the second year of the competition. (file)

When the infamous Willie Sutton was asked why he robbed banks, his reply was, “Because that’s where the money is.”

When you look at a map of the commuting patterns in the Birmingham metro area and you see all of the arrows pointing into Jefferson County, it’s pretty obvious that’s where the jobs are.

At last week’s Birmingham Business Alliance Regional Economic Summit, the BBA shared plenty of information regarding the metro area’s economy at the end of 2015.

While the focus was rightly on the number of jobs and the amount of capital investment announced with projects during the year, most telling was the geographic breakdown and commuting pattern maps.

It becomes abundantly clear that Jefferson County and Birmingham remain the economic drivers for the region and the state.

(Source: Office of Management and Budget, 2006-2010 Commuting Patters)

The map shows 45 percent of the workers in Blount and St. Clair counties drive into Jefferson County for their jobs. An additional 44 percent from Shelby County, 27 percent from Walker County, 23 percent from Bibb County and 11 percent from Chilton County bolster the fact the jobs are in Birmingham and Jefferson County.

Of all of the announced economic development projects in the seven-county metro area from 2011 through 2015, it comes as little surprise that most of the jobs and investment were in Birmingham and Jefferson County.

In that time frame, 8,975 of the 14,449 announced jobs in the metro area, or 62 percent, were in Jefferson County, and 6,163, or 43 percent, were in Birmingham.

For the same period, $2.1 billion of the $2.85 billion of announced investment dollars, or 73.3 percent, were in Jefferson County with $1.4 billion, or 49.7 percent, in the city of Birmingham.

Apart from Shelby County’s 10 percent of the jobs, no other county amassed a double-digit percentage of either the jobs or the investment dollars during that time frame.

But why?

One has to look at the economic development projects to answer that question. Three of the top five projects last year were expansions:

- Viva Health Inc. announced it was adding 400 jobs in its downtown Birmingham headquarters building.

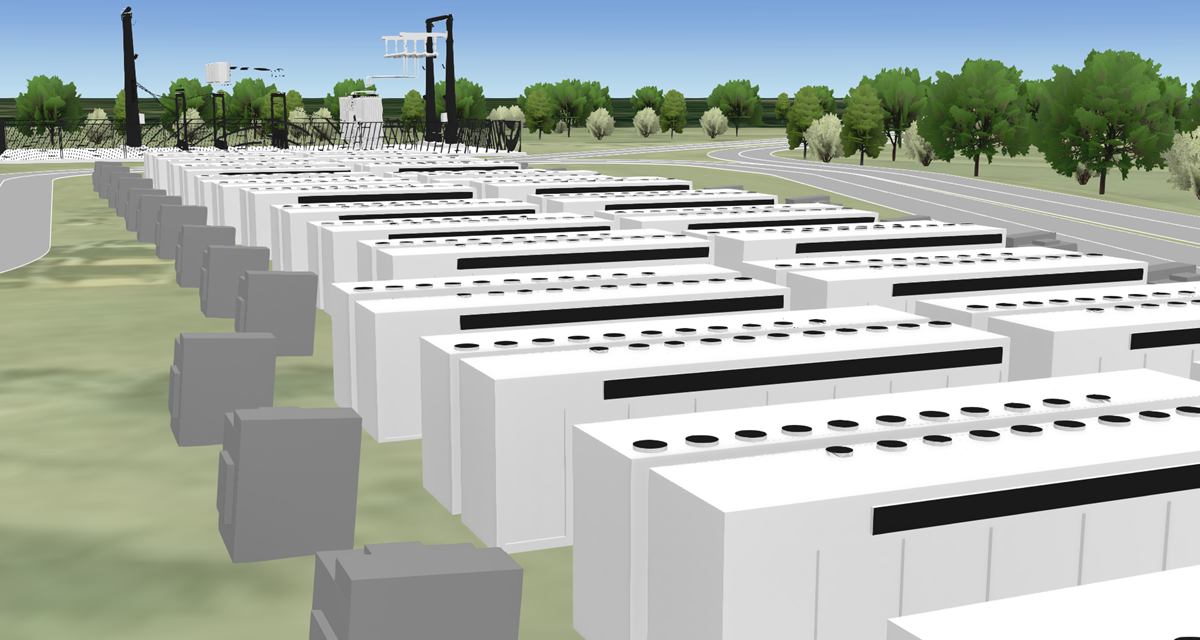

- Kamtek announced plans to invest $534.7 million and create 354 jobs with multiple expansions, chief among them an aluminum castings plant being built next to its operations in Birmingham’s Valley East Industrial Park.

- Wells Fargo said it is adding 300 jobs to its customer service center in Homewood.

The other projects in the top five were Yorozu Automotive Alabama, which is building an automotive supplier plant in a new industrial park in Walker County, and Publix Supermarkets, which chose the Jefferson Metropolitan Park in McCalla for a new $30 million distribution center.

The other projects in the top five were Yorozu Automotive Alabama, which is building an automotive supplier plant in a new industrial park in Walker County, and Publix Supermarkets, which chose the Jefferson Metropolitan Park in McCalla for a new $30 million distribution center.

In the three expansions, companies are choosing to grow in places where they are already successful. In the case of the other two, infrastructure improvements – new industrial park and Interstate 22 in Jasper and the established JeffMet Park in McCalla – were deciding factors.

Infrastructure is something companies in Birmingham and Jefferson County have spent decades establishing and nurturing. That includes roads, railways, water, sewer, fiber optics, electricity and gas as well as physical infrastructure like speculative office and industrial buildings and parks.

It helps that the largest employer and one of the main economic drivers in the state, UAB, is located at Birmingham’s core.

Can we expect to see the same trends five years from now, when the BBA issues its 2020 report?

Can we expect to see the same trends five years from now, when the BBA issues its 2020 report?

Maybe.

What might look substantially different is the commuter map, only because the next generation of workers may not want to commute.

Millennials have shown a desire to live, work and play in, or in close proximity to, urban areas. Fewer of this age group have aims on the larger single-family suburban homes and many are content to live in condos or smaller, older homes in revitalized neighborhoods like Avondale or Norwood.

Downtown development and renovation projects, along with sports, entertainment and recreational venues, are building on that trend in Birmingham – from Regions Field to Railroad Park to Rotary Trail.

The growth of Innovation Depot and plans to establish an Innovation District surrounding it will only fuel this fire and enable the next generation of workers to walk or bike to work instead of making a 45-minute commute.

The growth of Innovation Depot and plans to establish an Innovation District surrounding it will only fuel this fire and enable the next generation of workers to walk or bike to work instead of making a 45-minute commute.

Let’s not pretend that Birmingham has recovered from the “white flight” that hobbled it in recent decades or that all of its neighborhoods are enjoying the same kind of resurgence that some have seen. Crime and poverty remain issues in many of the communities and elected leaders haven’t always instilled confidence that those circumstances will improve.

Jefferson County has survived what was at the time the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history. With all of its successes in industrial development, the county is running out of shovel-ready sites to recruit industry and it doesn’t yet have the financial wherewithal to establish a new JeffMet.

Even so, there is no denying that the trends are positive for the city and the county to remain the economic heart for the region and, in turn, the state.

Michael Tomberlin is editor of Alabama NewsCenter and a veteran journalist who has covered economic development and business in the state for more than 20 years. Tomberlin’s Take is a column where he takes a closer look at a business or economic development issue.

Kamtek’s new $80 million casting plant will be producing parts later this year. (Kamtek)