Incompatible, yet needed: What are incompatible kidney transplants and why are they done?

Above: Vineeta Kumar (left) and Jayme Locke (center) meet with patient Ellen Herron, who received a new kidney in 2014 as part of a series of linked donations at UAB that is now the world’s longest kidney transplant chain.

The human body is primed to identify and destroy invaders like viruses, bacteria and other pathogens that can bring illness or death. Cells of the immune system and the antibodies they make recognize such foreign bodies and act to remove and destroy them.

This defense system is a potential problem for kidney transplants. People have different blood groups and different human leukocyte antigens that can provoke an attack if a tissue, such as a kidney, or blood is transferred from one person to another. These two barriers are called blood group incompatibility and tissue (or histo-) incompatibility.

A kidney transplant team uses the histocompatibility and blood bank testing laboratories to determine whether the tissues and blood group of a volunteer living kidney donor and the intended recipient match. A match is good, but matches are not always possible.

A kidney transplant team uses the histocompatibility and blood bank testing laboratories to determine whether the tissues and blood group of a volunteer living kidney donor and the intended recipient match. A match is good, but matches are not always possible.

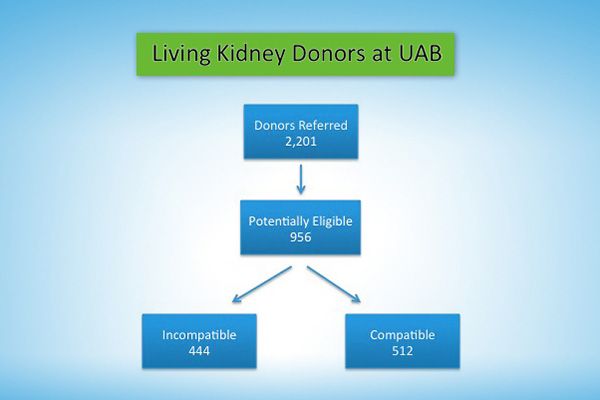

“Just based on blood group frequencies, about 35 percent of patients that come forward with living donors will be found to be blood group incompatible with their potential living donor,” said Jayme Locke, M.D., surgical director of the Incompatible Kidney and Kidney Paired Donation Programs in UAB’s School of Medicine. “Another 11 percent will be found to be incompatible based on tissue incompatibility. So almost half of patients are found to be incompatible with their potential living donors.”

By building a database of kidney patients and their potential living donors, the transplant team can look for paired exchanges, or swaps, where the potential donor of pair A matches with the intended recipient of pair B, and the potential donor of pair B matches with the intended recipient of pair A.

“Paired exchange requires a completely compatible match to be found,” Locke said. “This still leaves a very large group of disenfranchised patients; mainly patients who are what we call highly sensitized, or so sensitized that their hope of finding a completely compatible match is very, very slim.”

Those patients may still be candidates for a kidney transplant through UAB’s desensitization program. Desensitization allows survival of an incompatible kidney, using a variety of immunosuppression techniques.

How to desensitize

Protocols developed at various medical centers over the years involve the removal of reactive antibodies from the recipient’s blood before and after the transplant, giving drugs to lower the numbers of various reactive immune cells in the recipient, or reducing the ability of immune cells to respond and proliferate. Various desensitization protocols first emerged in the 1980s and began to gain greater traction about 20 years ago. This continues to be an important area of medical research throughout the world.

The two compatibility barriers are not equal – tissue incompatibility is a much greater problem.

The two compatibility barriers are not equal – tissue incompatibility is a much greater problem.

One measure of tissue incompatibility is the Panel Reactive Antibody test, or PRA, performed in a histocompatibility lab.

“PRA is a number that gives you some sense of how sensitized an individual is to all the potential donors in the pool,” Locke said. “For example, if you take one of our patients that was involved in a 2013 swap, her PRA was 99 percent. A good rule of thumb for the ability to find a match is something called the transplantability index. It’s 100 minus the PRA, and that tells us the likelihood to actually find a compatible transplant. So she had a 1 percent or less chance of actually finding a compatible transplant, either by waiting on the deceased donor list or continuing to bring in potential living donors.”

In the absence of an incompatible kidney transplant program, a patient like her had scant chance to find a compatible match. Instead, she would likely have spent the rest of her life on dialysis.

“For patients who are highly sensitized, we will overlook blood group compatibility and allow the computer to look through all the potential donors to try to find them a perfect tissue match,” Locke said. “We do that knowing that we will then have to cross the blood group barrier. But from the research that I’ve participated in and others have been involved in over the years, we know that blood group incompatibility is a lot easier to cross than tissue incompatibility.”

More than just quality of life

UAB began its paired exchange and incompatible transplant program in 2013, after years of preparation. Vera Hauptfeld, Ph.D., director of the histocompatibility lab, and Kumar made major contributions in putting the technologies in place and translating them to clinical practice.

But why do kidney transplants, even in the face of incompatibility?

Couldn’t patients with failed kidneys just continue their life-supporting kidney dialysis and let the machine remove excess waste, salts and fluid?

Vineeta Kumar, M.D., medical director of the UAB Incompatible Kidney Transplant Program, explains the answer.

“Compared to dialysis, a transplant offers not just quality of life; it is actually life-giving,” she said. “For every age group, starting from the pediatric age group to 70 year olds, or even higher, the life expectancy for transplants is far higher than with dialysis.”

“It makes sense that the younger you are, you are going to have more life-years gained because of the transplant,” Kumar said. “The older you are, your life expectancy is lower, so the life-years gained is not as much, but even in that category, a transplant is life-giving for the general population. If you have this modality that actually makes you live longer – and we’re talking 10, 20, 30 years longer – how can you not offer it to a patient?”

This life-giving essence of a kidney transplant persists even for incompatible matches.

“We know that patients who get a living donor transplant through our desensitization program have outcomes that are still far superior to remaining on dialysis, and they’re also superior to deceased donor kidney transplants,” Locke said. “If you look at outcomes among blood-group incompatible live-donor transplants, those outcomes are actually on par with compatible transplants. These patients do very well.”

“The tissue incompatible transplants aren’t quite as good but are still superior to deceased donor kidney transplants and certainly are far superior to remaining on dialysis,” Locke said. “If you look at tissue incompatible transplants eight years out, patient survival is somewhere in the 80 percent range. If we look at the same group of patients who were on dialysis, their survival is about 30 percent.”

“So it really does give patients life,” Locke said.